CCSD students tackle racism through education and activism

Approaching a downtown Atlanta intersection around 10 p.m., Kurali Grantham noticed an unlit police car parked in a lot to his right. Soon the car pulled out of the lot and up to the intersection. Grantham, nervous and fully focused on the officer, took care to use his turn signal before accidentally turning onto a one-way road.

Sirens blaring and lights flashing, the officer prompted Grantham to pull over. Kurali, who did not yet know why he was being pulled over, and his younger brother Copeland, who sat in the passenger seat, were startled and scared.

“When I saw the lights pull up behind me and I pulled over, I put my hands on the dashboard. I said, ‘Yes sir.’ I maintained everything that I had learned that my mom had taught me to do when interacting with a police officer,” Grantham said.

He announced his movements as he reached into his pocket for his wallet. Finally the officer gave Grantham a warning and walked back to his car.

This officer was only there to help him because he made the wrong turn, Grantham says. Nevertheless he believes he would not have made that turn if not for his fear after seeing the officer pull up behind him. Unlike at least 1,354 Black people killed at the hands of on-duty police officers in the last five years, Grantham is alive.

“What I learned in that situation was he was there to help me, I respected and even appreciated that, but that didn’t overshadow the fact that I was petrified when I saw his lights, when he walked up to my window, when he knocked on the car,” said Grantham, now a senior at Clarke Central High School where he leads a club that he co-founded called Students of Color Achieving and Pursuing Excellence (SCAPE), participates in mock trial, runs cross country and track, and has wrestled and played football.

“As I research police brutality and things like that, I’m not researching why I was thrown on the back of my car, why I was thrown on the ground, why I was beaten. I didn’t have that experience. But I understand and empathize with those who have, and I want to fight that so no one else has to,” Grantham said.

The Black Lives Matter movement began officially in July of 2013, when activist Alicia Garza coined the phrase “black lives matter” in a Facebook post. The post responded to neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman’s acquittal after fatally shooting 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. Since 2013, Garza’s hashtag has grown into a global social and political movement. Grantham says this movement is necessary.

“Black lives are under attack from these systems of racism. It’s not just resulting in a spiritual and emotional harm to the Black community, but physical harm. We have innocent Black men, Black women, Black children losing their lives due to people who these systems enable to take our lives,” he said.

Summer of 2020 brought a historic wave of protests tied to the Black Lives Matter movement. The movement this summer was sparked on May 25, when white Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd, a Black man. In the next week, people took to streets around the world to protest systemic racism and police brutality within the American criminal justice system.

The protests this summer were not in response to a new issue, rather a very old one. Black people have fought for a fair criminal justice system in America since Reconstruction. Kurali hopes that this movement will be different than those over the past decade.

“I think it goes to the notion of a tipping point. Society has known this is an issue, a pandemic, for a long time. I think that people are just getting fed up and are now having the courage to speak out against it. What’s different about this go around, is it will actually be a push and a grab for change,” Grantham said.

An even younger generation is taking notice as well.

“What’s really important is getting justice for us,” says Laila Nobles, a 5th grade student at Barnett Shoals Elementary School. “I don’t want anything bad to happen in the future for myself and others. You don’t really want a bad world, you want peace.”

She says sometimes she feels afraid of police officers herself, but especially for her father.

“My dad is a Black man. George Floyd died. He had a wrong $20 bill. They took his life, and I don’t want that to happen with my dad and him getting killed for nothing really,” Nobles said.

With Ebenezer Baptist Church West, she attended a silent Black Lives Matter protest on Juneteenth in Athens. Along with her parents and pastor, strangers on social media and TikTok in particular inspire Nobles.

“On TikTok, they give motivational speeches. It encourages me because it’s really inspiring words and it shows how they really care about (the Black Lives Matter movement),” Nobles said.

She says she is also inspired by women including Zendaya and Beyonce. Citing Beyonce’s “Black Parade” and “Black is King,” Nobles says art can be used to fight racism. She hopes to go to Columbia University in New York City and become a photographer and actor to make her own art.

Like Nobles, Cedar Shoals junior Aseel Mansour sees potential for positive change through social media platforms.

“I feel like social media and being able to see stuff firsthand has brought us closer with each other and how we’ve all been able to open our eyes and actually see what’s been happening in the world,” Mansour said.

A captain of the CSHS peer leadership program; member of outdoor club, Beta Club and the National Honor Society; and recently selected student ambassador for the Johnson & Johnson Bridge to Employment program, Mansour plans to attend medical school and pursue a career as either a pediatrician or a pathologist.

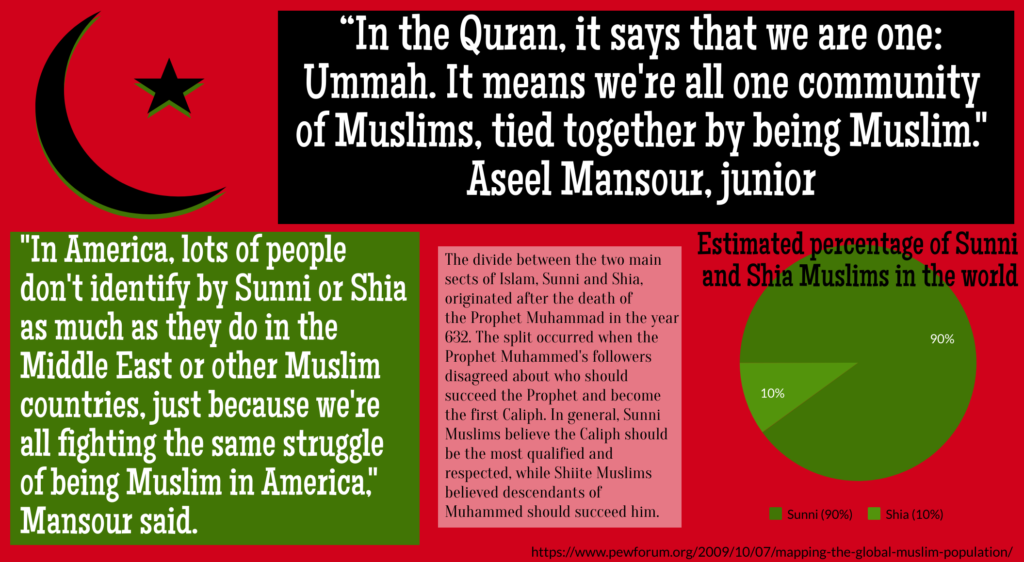

While Mansour has lived in Athens for her whole life, both of her parents were born in Sudan and some of Aseel’s family still lives there. As a Sudanese-American hijabi, she says she is stereotyped for the color of her skin and her Islamic faith.

“In fourth grade when we watched this documentary about 9/11, it was eye opening to lots of people and everybody started staring at me and I felt really overwhelmed. I had to leave the room. That’s when my mom had the talk with me about why people generalize people,” Mansour said.

The next day, Mansour’s mother came to school to talk to her teacher who suggested that Aseel put together a presentation for her class. Mansour taught her class about Islam, explaining why she wears a hijab and dispelling negative stereotypes. Still, she encounters intolerance.

“In seventh grade I had my hijab ripped off. I’ve had lots of stares in public. Nothing worse than having my hijab ripped off in seventh grade and maybe people peeking under, but since then I’ve gotten a lot of simple questions. I’m happy that lots of people have come to the realization that not all Muslims are bad and they can just ask me questions,” Mansour said.

Beyond being misunderstood by non-Muslim people, Mansour says lighter skinned Arab and South Asian Muslims treat her and other North African Muslims differently for their darker skin.

“Being one of the only Black families at my Mosque is kind of difficult. And lots of the teenage boys use the N-word. They just throw it around. There’s Arabic slurs toward Black people also that I’ve heard people use,” Mansour said.

At a statewide convention for Muslim youth in Georgia, Mansour witnessed boys saying they would not marry a woman whose skin was darker than their own. She says racism is not only an issue within her own mosque, but also on a more widespread cultural level.

“I think there’s definitely racism implanted in people’s cultures in the Middle East and South Asia. So I think a lot of the cultures implant this racism in their culture that it’s not good to be a darker shade of skin, and I know people try skin bleaching and all that type of stuff,” Mansour said.

Mansour says listening to the experiences of Black people and speaking up about them are some ways people can combat racism on both individual and widespread scales.

“I think our individual responsibilities are signing petitions, trying to spread the word, talking to our peers about it and in general having more open conversations about racism. I think people should be more open with each other, and it is hard to be vulnerable with people, but having those conversations with close friends, I think really would help,” Mansour said.

For students, some of these open conversations take place at school. It was in the peer leadership class at Cedar Shoals that Mansour says she began to understand the scope of police brutality in America. Her class watched a documentary about police brutality before discussing its contents as a class.

“I remember everyone in the classroom just kind of being shocked, because the classroom was mostly Black and Hispanic students. Ms. Johnson might’ve been the only white person in there,” Mansour said. “Everyone was kind of shocked and she was like, ‘You guys can take a minute to breathe.’ We all started having a big discussion. I felt like my world kind of shattered.”

However, peer leadership is an elective course, so it is not a required credit for students’ graduation. Mansour says while she and her classmates learn about slavery, Jim Crow laws and the history of racism, discussion of systemic racism today should be better incorporated into required curriculum.

“I feel like reading texts about it will really open up people’s eyes, and not even just reading texts, watching documentaries also helps, having conversations about it, like a Socratic seminar could really help,” Mansour said. Grantham has similar ideas for education on systemic racism.

“Diverse approaches to history are crucial to working towards a way of addressing systemic racism, for students. I hear the term all the time, ‘know your history,’ directed to Black people: the notion that our history is not in the textbooks, to a large extent,” Grantham said.

Nobles says the first time she learned about racism was talking about Harriet Tubman in school. But when it comes to learning about current issues, she suggests her peers take initiative.

“They can learn better by digging in more, researching, talking to me and asking me questions: ‘How does it feel?’” Nobles said. Even after public education up to 12th grade, Grantham says students need to be self motivated to learn about the challenges Black Americans face.

“I feel like that is one of the only ways youth can get an education on systemic racism in America is if you do it yourself, because we’re not talking about it in schools,” Grantham said.

Now Grantham is tackling a different, more personal facet of racial inequity. Motivated by their experiences as one of few students of color in many of their classes, Grantham and Rosario Sykes, a former Clarke Central student who graduated in 2020, co-founded SCAPE last year, aiming to encourage more students of color to take advanced or accelerated courses.

“I don’t want any other students to have the same experience that I—and many of the students of color—had of being one of few (students of color), when there’s so many more students with potential who can succeed in these classes. We want to help them realize their full academic potential,” Grantham said.

Both Grantham’s parents are professors at the University of Georgia. His mother teaches marketing and his father teaches educational psychology, specializing in gifted education.

“They were aware of some of the pathways and programs for gifted kids in elementary school, and they worked with teachers, gifted coordinators and my school’s administration to ensure I was exposed to the most rigorous and stimulating classes and environments available to me,” Grantham wrote in an email. He switched elementary schools twice before staying at Timothy Road Elementary School.

After elementary school, Grantham took some online classes in middle and high school that allowed him to enroll in required courses a year earlier than his peers. As he grew older he became more involved in making decisions about his education, but before he was making those decisions himself, he says his parents were fighting for him.

“The pushback my parents received stemmed from the belief that the accelerated agenda they were trying to push was impossible because it was different from the traditional pathway of many high-achieving students,” Grantham wrote.

The pushback Grantham received himself was more indirect and took the form of being one of few students of color in his classes.

“As far back as I can remember, my placement on the gifted track separated me from my peers of color, specifically my Black friends. As a young student, although I was mature and keen enough to notice the discrepancies between who was represented in gifted classes, I could not grapple with why that was the case,” Grantham wrote. “I began to feel isolated in middle and high school when the racial differences between much of my friend groups and classes forced me to adapt and behave differently in each environment.”

It was in an Advanced Placement (AP) Biology class with four students of color out of 32 total during Grantham’s sophomore year that he and Sykes started discussing their desire to change the disproportionate numbers of students of color in advanced and AP classes. The next year they started meeting with their sponsor-to-be, Dr. Ashlee Holsey, planning a way to achieve that goal through a club within their school. By the end of Grantham’s junior year SCAPE was official.

Grantham’s first cohort of SCAPE mentees includes 13 students. Although this year’s meetings, which begin on the third Friday in Nov., will exist on a digital platform, SCAPE meets regularly to provide support to students of color in particular in their current courses and push members to take more rigorous courses.

Grantham says in last year’s meetings, SCAPE mentees discussed their experiences in advanced and AP courses, ideas to create advanced and AP classrooms that are more demographically proportional to the rest of their school and strategies to succeed in challenging classes.

“We had conversations that went much longer than I anticipated, because they just opened up. It was amazing talking about our experiences, our interactions, our anger, things that have occurred in the classrooms and what I understood to be a sense of isolation that some of the students felt in their AP and advanced classes,” Grantham said. Because Sykes graduated and Grantham will graduate in 2021, he is in the process of finding a student to take over his leading role in the club next year.

According to data released by Clarke County School District from the 2017-18 school year, 81.3% of white students in the district graduated with AP credit, while only 47% of Hispanic students and 31% of Black students graduated with AP credit.

Grantham says this underrepresentation of students of color in more rigorous courses has complex causes.

“I think that lower expectations are detrimental in part to students of color in their pursuit of excellence. I think that the cultural differences and fear are also barriers to students of color enrolling in advanced AP classes,” Grantham said. “In my experience, many students of color don’t have some of the same supports at home that many of my white peers in my advanced classes have. As you’ve realized that you want to face these challenges, that your on level classes might be too easy for you, where do you find the support to do that from? If it’s not coming from home, if it is not coming from the school in the sense that you need it to come from, where is it going to come from?”

Mansour is both learning about and combating systemic racism in the criminal justice system in an internship through the Young Dawgs program at the University of Georgia, a program in which high school students can participate in internships for class credit. She takes a social psychology lab course in combination with a study on attitudes toward public officials including police officers, military officials and firefighters. Now she participates through a digital platform while continuing independent studies.

Mansour says that another part of fighting systemic racism in America is electing effective leaders and reforming the American partisan system to promote cooperation. She is a captain for a statewide organization called First to First. Its mission is to register new voters and increase youth voter turnout through organization of students.

“I like to just be like, ‘I’m Sudanese-American,’ and emphasize that I’m Sudanese first before I am American, especially since my parents are from there. But I mean I am proud to be American, and just being able to have so many rights that people in some countries don’t get to have,” said Mansour. “It makes me want to participate even more. That’s why I’m part of First to First, to try and get people to vote.” Mansour says that voter participation is important, but Americans also need to change the way politics work.

“I feel like the Democratic party and the Republican party are basically the same thing on two different sides of the political spectrum. They both talk about different things they want to change, but at the end of the day, do they really change them? No, not really,” Masour said. “I support abolishing the two-party system because if nobody has the moral obligations to fix anything in this country then nothing’s going to get fixed.”

Grantham plans to be a part of political change. After graduating, he hopes to attend college to learn about racism in the context of laws and politics. Following law school, he says running for a local, state or federal elected position is a possibility.

“Legislators take on a plethora of issues, not just issues in their field of interest. In addressing those issues, in writing those policies and making that legislation, I would maintain a perspective grounded in social justice, grounded in equity,” Grantham said.

Nobles, who plans to share her voice and make change through art, says everyone has to work towards tolerance and love in order to fix the issues of interpersonal and systemic racism.

“We just have to have love and not hate, and have peace. Even though there’s people on the other side, we need to know the real history and change history and make a better history for people in the future,” Nobles said.