Abolitionist teaching brings a new perspective to education

Facilitating conversations about racism in the classroom can be controversial and intimidating. Given the range of theories about when and how to have these discussions, some teachers might avoid the subject altogether.

Dr. Bettina Love, Athletic Association Professor in Education at the University of Georgia and co-founder of Abolitionist Teaching Network, says this avoidance of racial discussions is destructive to students and their communities.

“Abolitionist teaching is really about trying to create a school system that is loving, just and affirming to all students, not just Black and brown students, and to think about the policies, rules and procedures that are oppressive and unjust,” Dr. Love said.

She believes educators should emphasize not only the importance of discussing racism and injustices, but they must also show students that they—their cultures, their skin colors, their personalities—are beautiful inside and out.

“Abolitionist teaching is not about trying to reform a school system. It’s trying to say the school system needs to be dismantled so it can benefit all students,” Dr. Love said.

Jadzia Hutchings, Cedar Shoals math teacher, feels that school systems do not always have priorities that align with student needs.

“I think people aren’t doing abolitionist teaching or anti-racist teaching because they don’t feel the space for it. They’re too busy checking off all of those minimum boxes,” Hutchings said. “I think the public school system doesn’t trust its teachers enough. If we give an easy curriculum to a bunch of teachers that we can’t really trust, we at least know that something got done.”

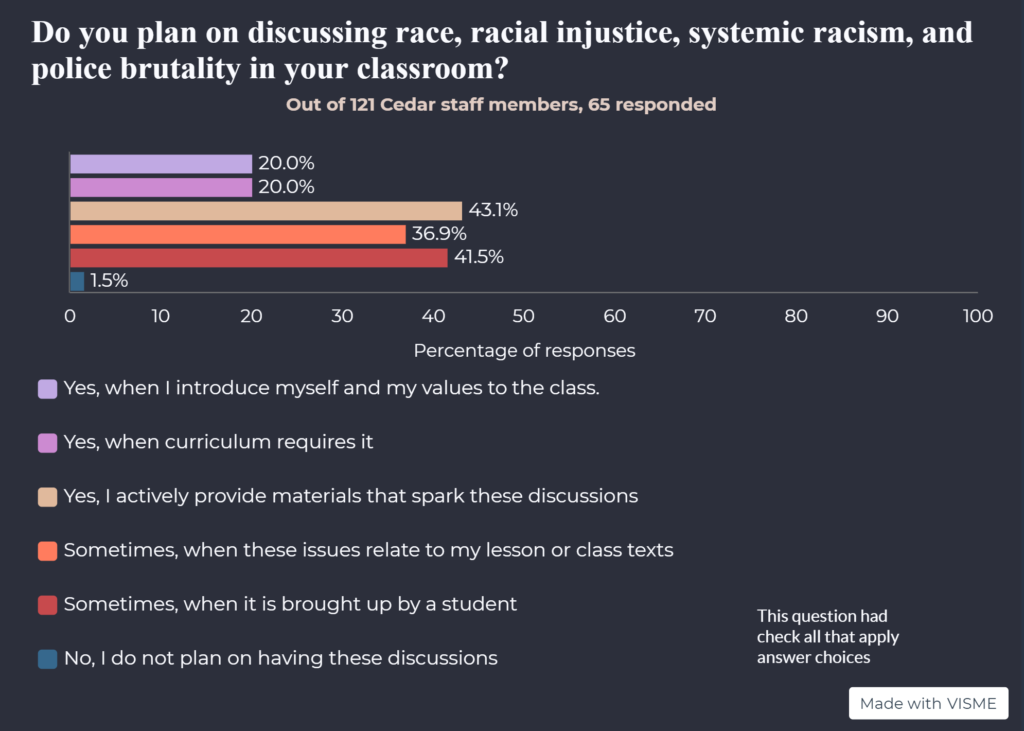

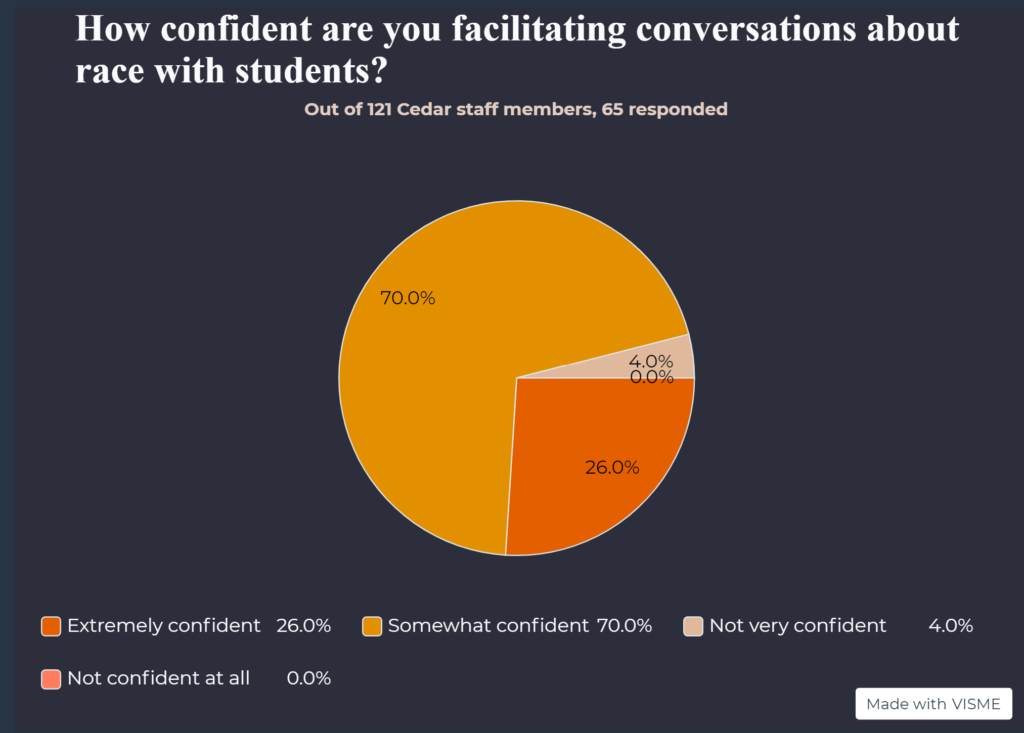

BluePrints Magazine conducted a survey to ask faculty if they think it is their responsibility to have open discussions about racism in their classroom, if they plan on discussing racial injustice in their classroom and whether or not they are confident in facilitating these conversations. The survey went out to 121 staff members and 65 classroom teachers completed it.

Although 70% of respondents said that they are somewhat confident in their ability to discuss racism and many said that they actively provide materials to spark these conversations, students still express that they cannot remember having any discussion about systemic racism, racial injustice or police brutality throughout their years in school.

Senior Chloe Christian recalls bringing up the recent protests to dismantle systemic racism and attempted to provoke a class discussion, but she was not acknowledged.

“(The teacher) ignored what I was really talking about and continued on with the lesson. I gave her the benefit of the doubt because she was in the middle of a lesson, but it’s not something to ignore,” Christian said.

Sophomore Marcus Welch believes that teachers want to have these conversations, and they think that they are having these discussions while in reality they are not.

“I think everyone wants to feel like they’re doing their part to make things better. I think maybe teachers are feeling like they’re doing a lot for their students when it comes to talking about these sorts of things. But when it really boils down to it, they aren’t doing as much they feel like they are,” Welch said.

From his experience, he recommends that teachers avoid shutting down conversations about race.

“If you aren’t going to be the one to initiate the conversation, but the conversation somehow starts, don’t stop it,” Welch said.

Freshman India Collins says that some space for discussion about racism has been opened in her film class, but it has not been brought up in her other classes.

“We do discuss it and the importance of it in my film class,” Collins said. “Sadly I think the only time when we talked about it (in other classes) was Black History Month, and it was only for a day or two. So I don’t think we talked about it as much as we should.”

Ana Mowrer, 9th grade, explains that there have not been any discussions about racial injustice, police brutality and systemic racism this year in her classes. She recalls conversations about racism, but only in a historical context.

“It’s more history wise; it’s not current racism. But we have talked about the injustices in the past with Jim Crow laws and things like that, but not really in a systemic sense,” Mowrer said. “I think a lot of teachers aren’t educated on it, or they don’t feel comfortable talking about it.”

Even though these students voice disappointment, many recognize the difficulty for teachers to facilitate these conversations. Cedar teachers talk about the difficulty of discussing racism and political events when they are still processing racism in America and its devastating effects. They also explain that often it’s hard to find the balance of what is ethical to say according to school regulations and society’s standards.

“We have to take this in, and every single week now there are reports of physical abuse, of people being murdered. We have the right as a person, not just as a teacher, to be completely freaked out by all of this. Because it’s a lot,” Caroline Bharucha, world language department, said.

Some teachers are struggling with how to teach their curriculum virtually and support students from afar.

“We come with our own flaws. We come with our own sets of knowledge, our own culture, traditions, beliefs, etc. You’re asking teachers not only to teach the curriculum, because that’s our job, but then you also ask us to now become social workers, activists, so many things. We have to have the right to grow as well,” Bharucha said.

Teachers should not have to feel like they are on their own. Dr. Love believes that if teachers had more training on constructive discussions with students about race and culture, then it would be easier to implement abolitionist teaching.

“A teacher is only going to teach what he or she or they know. We folkx who teach teachers need to expose them to these conversations earlier in their teacher education program. If we don’t teach them how to have these conversations, how to engage with people, how to be critical of the system, they’re not all of a sudden going to know how to do this,” Dr. Love said.

Hutchings believes in implementing abolitionist teaching into more classrooms at Cedar Shoals, making sure students have the opportunity to bring up topics that relate to their lives.

“I want my students to feel like they’re heard. And if the things that they want to talk about are racial injustice, then we have room for that and we make space for that. I don’t think that it’s okay to never let the conversation come up,” Hutchings said.

Brittany Moore, English department, notes the difficulty in finding the balance between staying impartial while having a positive impact on students.

“It is a responsibility of teachers to help students navigate the real world—even if that world is contentious and politically charged. It is also an ethical responsibility of teachers to not push their personal politics. Bias also exists in absence,” Moore said.

Moore talks about the importance of raising these issues, because when teachers avoid certain topics, silence can be destructive. That avoidance starts as early as elementary school.

That absence of truth deeply affected freshman Karmen Carter, who recalls learning a whitewashed and watered-down version of slavery. When her mom asked her what she learned about slavery in school, Carter responded, “Oh that’s not that bad.”

In response, Carter’s mom showed her “Roots,” first a novel and then a screenplay written by Alex Haley, telling the story of Kunta Kinte, an 18th-century African who was taken from his native land and transported to North America to be enslaved and violently abused by slave owners. The story follows Kinte’s life and then his descendants down to Haley.

When Carter saw “Roots,” she realized that her teachers had not told the truth.

“I remember being so betrayed. Like my teachers lied to my face. That wasn’t the truth. In my mind, I was like, ‘Well, how am I ever going to trust them again?’ That trust was completely broken. Yeah, it’s school regulation, it’s county regulation, but once you lose a child’s trust, it’s really hard to earn it back. Teachers should fight for that. They should fight for that choice,” Carter said.

Dr. Love agrees that teachers should advocate for teaching the full history of oppression in America. She says glossing over injustice “lowers a student’s self-esteem, because they don’t see themselves, they don’t see their history, they don’t see their language.”

While some students are disappointed in the education system, others believe that it is not always the teacher’s responsibility to facilitate discussions concerning systemic racism.

“It’s not really in their job description,” said Robert Chatmon, an 8th grader at Hilsman Middle School.

Chatmon believes that every time a teacher opens their mouth to say something political or controversial they have to decide whether it’s worth it because the consequences for teachers talking about racism can be more drastic than the benefits.

“There are many things that teachers would like to say on this matter, but they can’t really say it because their job is in the way. That’s what teachers have to do, that’s what teachers have to debate with every time they open their mouth. I just know it’s hard,” Chatmon said.

The consequences for sharing their political views have led to teachers being fired. In Dallas, Texas, a teacher was fired for refusing to replace a mask that read “Black Lives Matter” and “Silence is Violence.” Taylor Lifka, an English teacher Roma High School in Texas, was put on administrative leave for having posters in her classroom that supported the Black Lives Matter movement and an LGBTQ flag. Gwinnett County middle school teacher Paige McGaughey was criticized for having a Black Lives Matter poster in her classroom.

At Cedar Shoals, the BluePrints survey results suggest that the majority of faculty respondents want to have these conversations with students. Still, student perceptions of their own experiences in classrooms indicate that teachers may need more support. Dr. Love offers solutions for building communal, civically engaged schools and equitable classrooms. To combat systemic racism, she says, communities have to reimagine the educational system itself.

“One of the first steps is to think very deeply about how we fund schools and inequalities in schools. A big reason why teachers feel like they can’t (implement abolitionist teaching) is because they have standardized tests now, and they have to teach to the test. We’ve got to replace standardized testing with a rich curriculum that’s not created by curriculum companies, but by communities,” Dr. Love said.

While reenvisioning a richer curriculum created by communities will be a long process, there are ways that teachers can integrate Dr. Love’s practices into their daily lessons now.

“We’ve got to get to a point where we’re going to tell history from multiple perspectives, from multiple viewpoints. This is how you have a society that critically thinks when you expose them to multiple points of view, multiple ways of thinking, multiple histories, multiple perspectives. I don’t just want Black history. I want them to learn about Irish people, I want to learn about Jewish people, I want them to learn about Hispanic people,” Dr. Love said.

In tackling difficult conversations about systemic racism, Dr. Love believes that educators should go beyond tragedies like the events last summer. Rather, to create classrooms where students are loved and taught to respect each other’s cultures, skin colors and personalities, she urges teachers to also focus on better establishing Black people’s humanity.

“I want students to know about racism, but I also want students to know about the contributions of Black people and Indigenous people, and brown people. I want them to know about their creativity, their love and joy. So another way to think about teaching about racism is also teaching about people’s humanity, why people are beautiful, why people are loving, why people are kind. Telling people about Black people dying, telling people about Black people and injustice, that does expose them to these issues, but what’s going to make them understand Black people’s humanity is to show them who we are. Show them why we’re loving, show them about our culture and our history. That’s also anti-racist education,” Dr. Love said.

Teachers may still experience internal struggles in approaching these conversations, but inviting dialogue is a step in creating a safe, loving and affirming environment for students with different cultural backgrounds.

“The real change of this country is going to be thinking about how we get together and think about systematic change. But we do that together in community,” Dr. Love said.