Cedar Shoals alumni participate in the Moderna vaccine trial

Neal Browning and Doug Lloyd barely knew each other when they graduated from Cedar Shoals in 1991, but now the two have been brought together over social media by their participation in the Moderna vaccine trial.

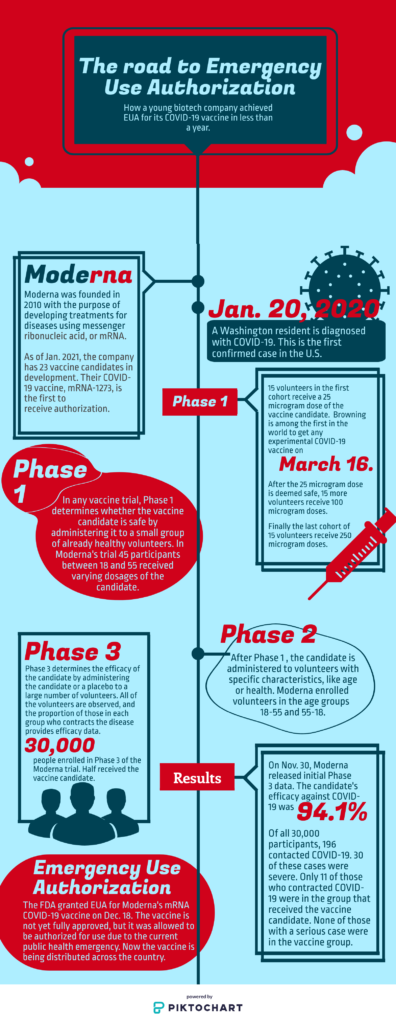

Browning, a Phase 1 volunteer, was the second person in the world to receive an experimental COVID-19 vaccine. Five months later Lloyd was one of half the 30,000 volunteers in Phase 3 to receive the emergency use authorized mRNA-1273.

“The first confirmed case and the outbreaks were each about five miles from where I live right now. So I was literally in the epicenter of this as it was happening,” Browning said.

A network engineer for Microsoft in Bothell, Washington, Browning submitted his name to a lottery after a friend suggested he participate in the vaccine trial. After a medical background check, he was officially selected for the program.

Browning, whose wife and mother are registered nurses, was motivated to participate in the vaccine trial in part for Moderna’s mRNA vaccine, a new approach to inoculation. No mRNA vaccine has been granted EUA or full approval by the FDA before now.

“I talked to my mom and I talked to my wife, to both lean on their medical expertise and background and get their take on it. I explained how it worked,” Browning said. “And they said, ‘This actually is a really cool approach. It seems like one of the worst case scenarios is you get a little bit sick and the other worst case scenario is for the pharmaceutical company, that it doesn’t work and your body just ignores it. So it seems like the risk is very low, the rewards could be incredibly high if this helps out mankind, I think you should do it.’”

Browning was greeted by a team of Associated Press reporters upon arrival at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle on March 16. He checked in with the receptionist and received a parking waiver. Within ten minutes he was on his way to a private room.

Before getting the shot, the clinic’s staff checked Browning’s blood pressure, conducted a physical and drew blood.

“Then the pharmacist came in with a little clear plastic baggie that he’s holding very delicately, and it’s got the needle inside with a big orange biohazard sticker on it. I’m like, ‘OK this is getting real now.’ And I’ve got two guys from the Associated Press standing in the doorway, taking pictures rapid fire. Then he stuck the needle in and it almost felt like nothing,” Browning said.

He spent the following hour scrolling through social media and answering emails in between periodic checks from clinic staff. Browning reported no side effects apart from a brief and subtle soreness at the injection site the next morning.

After all 45 Phase 1 participants received both doses of the vaccine candidate, volunteers’ blood samples were compared to those of people who contracted COVID-19. Those who received the 100 microgram vaccine had 4.1 times the neutralizing antibody levels than those who previously contracted COVID-19.

Browning likens the spikes found on the surface of the new coronavirus to a hypodermic needle. They stick to the surface of human cells in the airway before transferring the virus’ genes into the cell. Consequently, these infected human cells begin to make more coronaviruses, repeating the process.

“So the neutralizing antibodies are the important ones, because they actually cover that spike. And if you have enough in your bloodstream, they will cover every spike on every virus, neutralizing it where it can’t infect other cells. That’s what prevents you from getting infected and making you immune,” Browning said.

Lloyd, an Athens resident, volunteered for a study looking at the behavior of these antibodies. Project SPARTA, or SARS SeroPrevalence and Respiratory Tract Assessment, is a study based at the University of Georgia aiming to measure antibody levels after COVID-19 infection. After receiving both injections during Phase 3 of the trial, Lloyd volunteered for Project SPARTA.

He works as a systems administrator specialist and provides technology support at the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences at UGA. Lloyd has worked from home since March, and has never contracted COVID-19 to his knowledge.

Lloyd learned through Project SPARTA that when he participated in the Moderna vaccine trial he received the vaccine candidate instead of the placebo. After regular negative COVID-19 test results, the researchers found antibodies for the virus in Lloyd’s blood. Although Lloyd did not develop antibodies due to infection with the coronavirus, his participation in a vaccine trial did not disqualify him for Project SPARTA.

On Jan. 14 Lloyd received a completed vaccine card, confirming he had been vaccinated against COVID-19.

In the summer of 2020, Lloyd’s sister reached out to him to ask if he knew about the Moderna vaccine trial. He signed up online to participate and submitted his personal information on the Moderna website. Then the Emory Hope Vaccine Clinic reached out to Lloyd. In a 15 minute phone call Lloyd shared his medical information, learned what the trial would entail, and confirmed his willingness to participate.

One factor in his decision to participate in the Moderna trial was the possibility of being inoculated against COVID-19.

“I really felt like people who haven’t been able to have a voice in the world right now need folks like me who are loud and are willing to stand up for folks who have been oppressed or who have had some type of challenge and don’t necessarily get the same opportunities some of us get,” Lloyd said. “I definitely didn’t want to be a victim of the coronavirus, so I wanted to do something to help, but also in a way make sure my voice was here to be heard.”

Additionally, he chose to volunteer to help diversify the participant pool.

“When they got to phase three, they were looking for a more diverse subset of patients. Before the pandemic started, I considered myself morbidly obese. With obesity and high blood pressure being two of the high risk factors, since I’m otherwise healthy, I thought I might be a good candidate to participate in the trial,” Lloyd said.

Lloyd arrived at the Emory Hope Vaccine Clinic on Aug. 12 to receive the first injection. Clinic staff conducted a COVID-19 test and drew blood to test for antibodies before giving Lloyd the first injection.

In between the first and second injections, Lloyd and the other participants provided daily status reports in an “E-Diary.” Lloyd logged a headache the evening of the 12th and received a call from the clinic the next morning. Lloyd’s headache was gone, but soreness in his arm lasted three days.

On Sept. 9, Lloyd received his second injection, 28 days after the first.

“I got a full work up by the doctor at the Emory clinic that day. They’re checking lymph nodes in particular because that’s where the mRNA vaccine, if you’re going to see side effects, it’s going to be in the lymph nodes systems. They do another nasal swab, take eight small vials of blood again, and get the full physical, and then the nurse comes in to do the injection,” Lloyd said.

The nurse who gave Lloyd the second injection identified herself as an “unblind worker,” meaning she knew which kind of injection he was getting. But Lloyd says the syringe itself had a label taped to it that read “COVID-19 vaccine or placebo” to prevent him from knowing which kind of injection he would receive.

Lloyd developed another headache three hours after the injection, logged the headache and a slight soreness at the injection site and went to bed.

“The next day, at about 30 hours post injection time, I started to get chills. I got the thermometer, and sure enough I was running a fever. My normal body temp is usually about 97.4. When I went to check my temperature it was about 100,” Lloyd said. The fever and chills were gone the next morning.

Half of the participants in Phase 3 received a placebo. The trial is double-blind, meaning neither the participants nor the scientists know which volunteers receive the vaccine candidate versus the placebo. But Lloyd’s side effects, along with the antibody test he would later take through Project SPARTA, provided strong evidence that he received the candidate.

The results of Phase 3 of the Moderna trial, released Nov. 30, found the candidate had 94.1% efficacy. 196 out of 30,000 participants contracted COVID-19. 11 of these participants received the vaccine candidate instead of the placebo. Of the 11 who received the candidate and contracted COVID-19, zero participants had severe symptoms.

On Dec. 17, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee voted in support of granting Emergency Use Authorization for the Massachusetts based biotechnology company’s vaccine.

The next day, the FDA granted EUA for Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine for the prevention of coronavirus in individuals ages 18 and up. The administration granted EUA for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, for individuals 16 and older, on Dec. 11.

Pfizer and Moderna achieved EUA for their vaccines faster than any vaccine in American history.

“I think some of the things that our executive administration in the US has done as far as removing some of the red tape has helped move us forward faster with the vaccine,” Lloyd said. “I don’t see that that speed is coming at a cost of safety. The current speed is coming from advances in technology, specifically like these e-diaries, being able to decentralize all of the clinics that they’re doing the tests in. We’re doing a much better job being able to get a subset of America, versus when the polio vaccine, chicken pox vaccines and other things were being developed.”

The EUA allowed Moderna to begin distributing its vaccine. As of Jan. 26, 19.9 million people received at least the first dose of one of the two COVID-19 vaccines. 23.5 million total doses have been administered, 10.4 million of which were the Moderna vaccine. A total of 44.4 million doses have been distributed.

“I’ve been hopeful ever since I’ve seen the results from the Modera and Pfizer studies,” Browning said. “There are hundreds of millions of people in just this country, and there are billions in the world. They can only make the vaccine so quickly, they can only distribute it so fast, there are going to be constraints.You can literally only move as fast as the slowest link in your supply chain.”

The reported number of doses administered is an underestimate due to lags in reporting. Still vaccine roll-out is slower than experts hoped.

“I do see there being a turning point by probably summer time if we get enough people on board and get enough people to understand that this is safe. This is something important they need to do, and they’re still not doing the mask thing, and the hand washing, and the social distancing—this is your last chance to do it right with the vaccine,” Browning said.