Growing gifted: CCSD program is evolving to become more inclusive

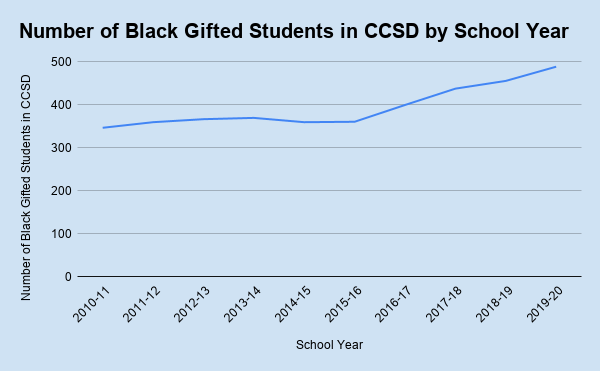

From 2010 to 2020, CCSD’s gifted program grew by 43%, which is eight times greater than the growth of the CCSD student population during the same period. Still, in the last ten years, 57% of gifted students were white or Asian in a district that is 78% Black, Hispanic, and multiracial students. Although they make up half of the CCSD student population, by 2020, only 7% of CCSD’s Black students were identified as gifted.

Cedar Shoals sophomore Jayivey Brown is one of those students. Growing up as a minority in the program, Brown remembers the stigma that she felt.

“When they would pull us out of class to go to the trailers, on multiple occasions, if it wasn’t the actual teacher coming to get us, I would get up and either my homeroom teacher or the person coming to get us would be like, ‘Sweetie sit down’ because they would be surprised that I was the one getting up because I’d be the only Black kid getting up,” Brown said.

Dr. Jennifer Bogdanich, CCSD’s gifted program coordinator since August 2020, says that the program strives to be as inclusive as possible through different equity initiatives.

“A few of our equity initiatives are to increase participation in our gifted and advanced programming, especially for underrepresented students, by using a variety of testing measures to minimize cultural bias, implementing universal screeners to all students for early identification and recognition of talent, and training all teachers to have an assets-based mindset to inform gifted identification and teaching and learning,” Bogdanich said.

Whit Davis Elementary School gifted teacher Jennifer Biddle agrees the program has been working to become more equitable over the past ten years.

“We definitely still have more white folks in the gifted program, we just do. We try our best and we have more Hispanic kids than we’ve ever had before, which is great. We’re trying our best to have a diverse representation all around,” Biddle said.

While the percentage of Hispanic students in the gifted program increased by 71% over the last decade, the percentage of newly added students who are Hispanic trended downward over the ten-year period, from 22% of new gifted students in 2010 to 15% in 2020. Although CCSD’s Hispanic population has grown by 17% over the past decade, by the end of 2020, 11% were identified as gifted.

Improvement initiatives

CCSD’s gifted department is working to make the program more equitable. Through the Talented and Gifted Checklist, the Students of Promise program, a gifted endorsement program for teachers and equity meetings, the program is becoming more inclusive.

In 2019, CCSD began using the Talented and Gifted Checklist, a new referral process which had been used in Atlanta Public Schools to decide which students to test for the gifted program. Teachers use the checklist to see if a student has gifted behavior characteristics such as leadership, creativity, advanced academic ability and motivation. Depending on the student’s evaluation, an eligibility committee will discuss whether to go forward with testing.

“So instead of just saying, ‘Who in my class demonstrates these attributes? Well, let me think off the top of my head,’ it’s a more data-driven approach where every student is appreciated,” Whit Davis Elementary School gifted teacher Lindsey Davis said.

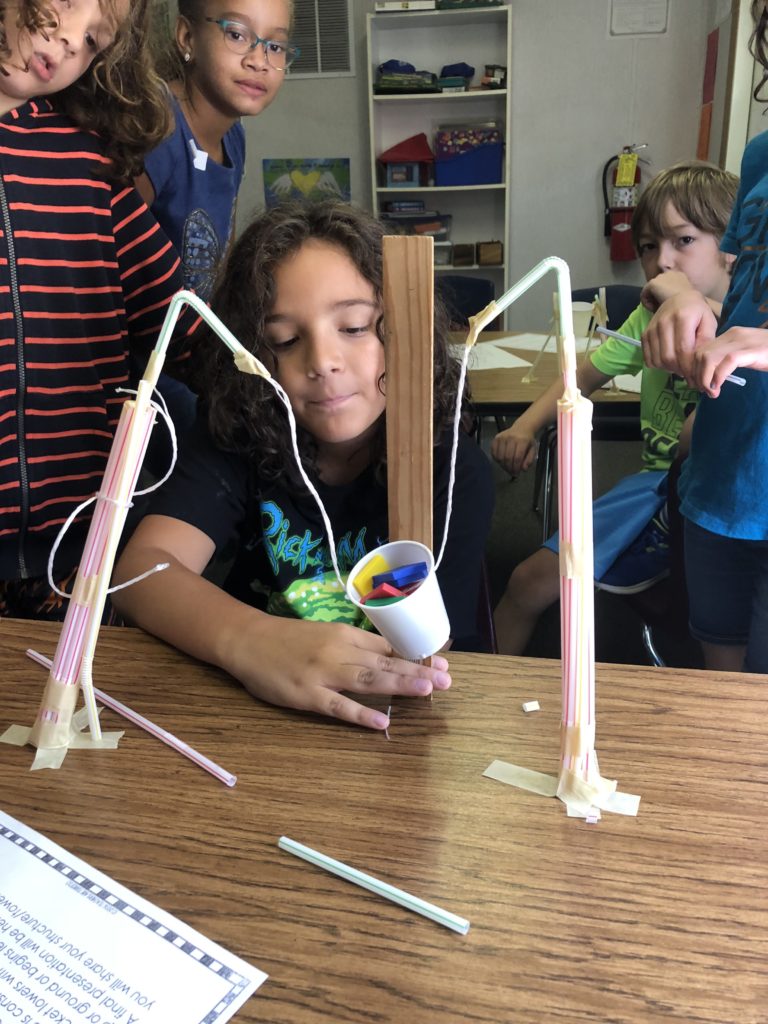

Separate from the gifted program, the Students of Promise program, put into place in 2005, identifies potentially gifted students in kindergarten through second grade from populations underrepresented in the gifted program and provides them with enrichment activities. Approximately 50% of the students that have completed the program qualify for the gifted program.

Karen Higginbotham, a former gifted teacher for Fowler Drive Elementary School, served in one of the pilot classrooms during the implementation of the Students of Promise program. Higginbotham, who would later become a gifted coordinator for CCSD, says the program has been successful in diversifying the gifted program and enabling a wider variety of students to receive gifted learning opportunities.

“There were units of study around some of the books or autobiographies we would read during that time like Oprah Winfrey, Frida Kahlo, George Washington Carver, Martin Luther King, a series of underrepresented folks who have exceeded or demonstrated the same type of strength,” Higginbotham said. “Part of the idea behind that was to build in (students) the ability to see people like them who came from a lower socioeconomic status, who were able to overcome and be successful.”

CCSD is also working to expand gifted teaching through gifted endorsement programs. Every year, 50 CCSD teachers participate in a one-year training, equivalent to four graduate-level courses, to become gifted endorsed. Currently 27% of CCSD teachers are gifted endorsed. Bogdanich says this training allows a wider range of students to benefit from gifted teaching.

“All students benefit when their teachers are equipped with gifted instructional strategies, as these strategies increase student engagement and higher-order thinking,” Bogdanich said.

Both elementary and middle school gifted teachers take part in equity meetings every month, where they look at the program’s racial makeup and different tactics being used to increase diversity. Davis says these meetings promote discussions on how to evolve the program.

“We’ll open the meeting up and then we break into small groups, and I might be with a gifted teacher from J.J. Harris, Fowler or Barnett Shoals. We’re all from different schools and we’re talking about, for example, with the questionnaire, ‘How is that working for you? What obstacles are you finding?’ And then we’ll come back and say, ‘Has it been successful? What are your numbers?’” Davis said.

Room for improvement

To be accepted into the gifted program, the state of Georgia requires students to qualify in three out of four categories: motivation, creativity, mental ability, and achievement — or have a qualifying score in both the mental ability and achievement categories. Additionally, those who qualify in only two categories and create a portfolio may be accepted into the program.

One example of a tool used to evaluate for creativity is the Torrance Test for Creative Thinking, where students may have to use their imagination to create a story with pictures. Students must score in the 90th percentile for this category to qualify for the gifted program. The state testing guidelines provide several ways to evaluate students in the different categories, and teachers are constantly evaluating the different tests for signs of bias, according to Davis. For example, questions on some tests may rely upon prior knowledge of items that may not be present in every student’s home.

“A lot of people think that we’re not equitable in our testing or that there are not enough minorities in gifted because we should have the same percentage represented that we have in school in our gifted program, and we don’t,” Biddle said. “Maybe the tests are a little biased and I wish we could really focus on those tests and change the tests we give, but the state tells us what tests we can give for the kids to qualify.”

Hilsman Middle School eighth grader Finn McGreevy tested for the gifted program without success until this year. She describes self-induced pressure to get into the program.

“Every single one of my siblings had been in it, so I felt like I wasn’t living up to an expectation that my family had,” McGreevy said. “It was never really vocalized, but I was like, ‘I’m not as good as my siblings because they’re winning awards because the gifted program gave them time to work on science fair projects.’”

Brown also recognizes the exclusion that students outside of the program may feel.

“It kind of made certain students feel more inferior because they weren’t being taken out of class to go on a QR code scavenger hunt around the school,” Brown said, referencing the kind of high-engagement activities that gifted students have taken part in.

In some schools, students are pulled out of class to go to a gifted classroom during extended learning time (ELT). Other schools such as Whit Davis have moved away from ELT, helping to combat the separation between those in gifted classes and those who are not. Davis now works with students by visiting classes rather than pulling students out.

“If I’ve come in to serve your classroom, I’m serving every child. I’m working in a small group with the students that are struggling to read. I’m co-teaching with a teacher,” Davis said. “I will teach the same math activity, but I’ll differentiate it for each group that comes.”

Future academic achievement

The gifted program in high school is partly composed of advanced content courses, classes that students can select during registration. In 2021, 728 of Cedar Shoals’ 1,400 students are enrolled in advanced content classes (not including Career Academy). The smallest of these classes is AP Chemistry with three total students.

Cedar Shoals sophomore Marcus Welch says that the gifted program motivated him to take more advanced classes.

“It allowed me to have an easier time when it comes to getting into accelerated classes and advanced classes, and obviously that looks better. It’s almost like a domino effect. I definitely think being in the program helped me,” Welch said.

Although the high school gifted program primarily consists of courses that students can choose to take, in middle school the state requires defined testing criteria which may limit participation. To qualify for advanced content courses in fifth through eighth grade, students are reviewed using I-Ready test results, grades and teacher recommendations. Cedar Shoals gifted coordinator Stephen Castile believes the middle school criteria may be a barrier to getting more high school students enrolled in advanced content courses.

“There’s far greater criteria to be in those classes in middle school. I feel like we’re missing a good number of students in some of those advanced courses who could be doing that level of work but don’t meet the (earlier) criteria. I believe the criteria are evolving, for lack of a better word, to try to be more inclusive and allow not just more diverse kids but a greater number of kids in those courses,” Castile said.

Going forward

From 2010 to 2020, the number of white students in the gifted program increased from 796 to 1,198 students, and the proportion of the gifted program that was white increased slightly from 51% to 53%. By 2020, 39% of CCSD’s white student population was identified as gifted.

“It is still heavily the white students, but that leads me back to testing. That’s where it needs to start. We need to analyze those tests and we need to talk to the state about either changing them or to the publishers about rewriting them,” Biddle said.

Biddle also wishes that there was less emphasis on standardized testing to allow for more flexibility in teaching.

“I don’t necessarily think we need more pullouts, but I wish more teachers were able to do more engaging projects in class. We are so pressured to have our students perform on these standardized tests that we feel we don’t have the time to do that,” Biddle said.

Davis, who doesn’t call herself “the gifted teacher” around students, knows that by interacting with all types of students and eliminating bias, CCSD can show that the gifted program is for everyone.

“Giftedness is not one size fits all. Human beings are complex and everyone’s so special and so different. We really need to capitalize on that in our school district,” Davis said.