Tracing trials: districtwide COVID-19 mitigation requires new hires, communication changes

A contact tracing team made up of current and retired school nurses, students in the University of Georgia College of Public Health and Clarke County School District Director of Nursing Amy Roark is at the center of COVID-19 mitigation in CCSD.

“In terms of taking care of ourselves and each other, the most important thing you can do is get vaccinated, the second most important thing you can do is wear a mask,” Dr. Grace Bagwell Adams, UGA College of Public Health, said. “When you think about our approach to pandemic control, those are two legs on a three-legged stool and the third leg is testing and tracing.”

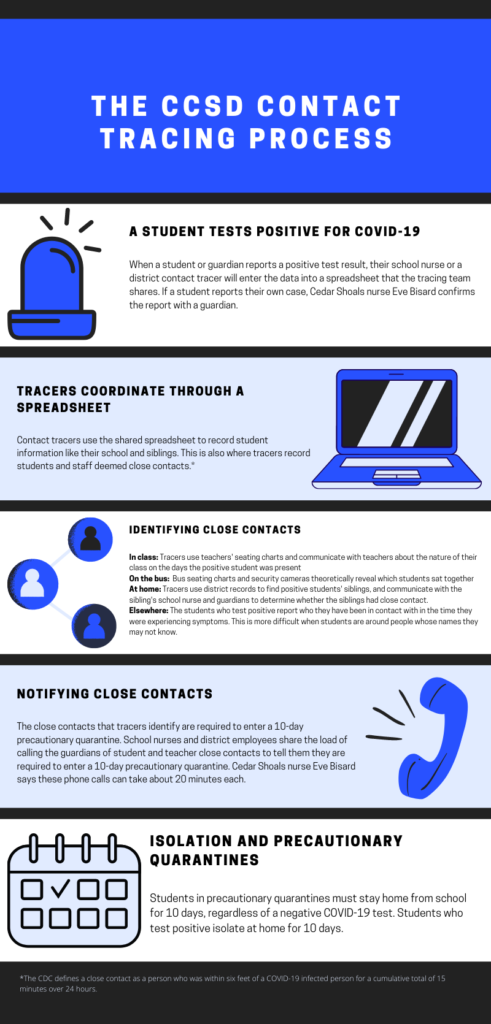

Contact tracing requires collecting data on positive cases of a disease, determining close contacts of these individuals and advising contacts on how to prevent spread. CCSD has practiced contact tracing throughout the pandemic, but with schools returning to full in-person instruction, the process is more complex than before. High schools in particular pose their own set of challenges for tracing.

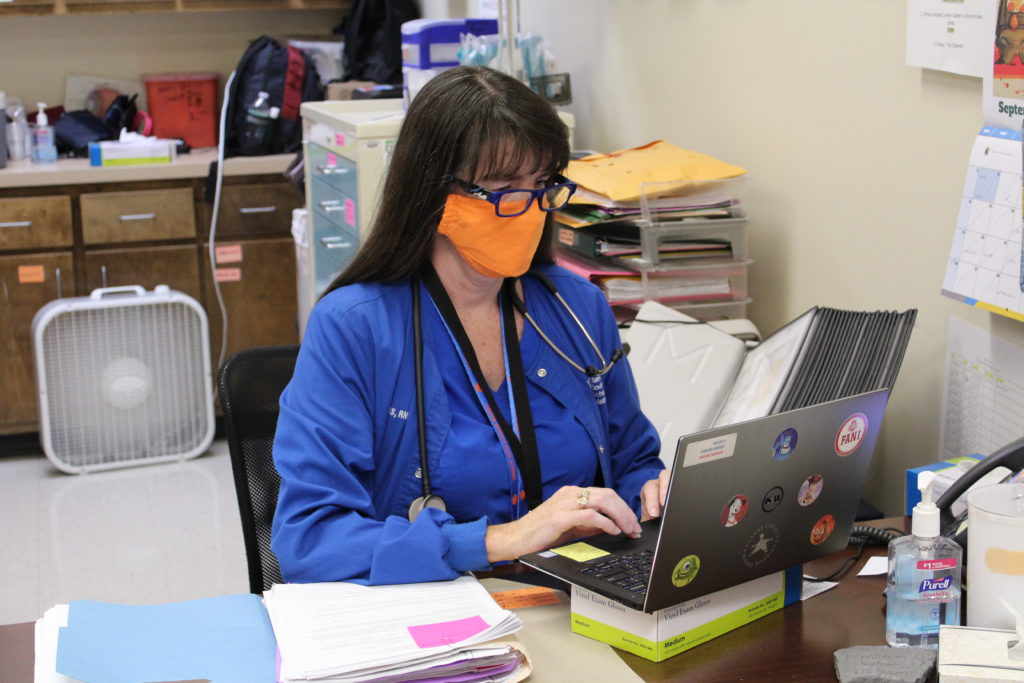

At Cedar Shoals High School, contact tracing begins when school nurse Eve Bisard or another member of the district contact tracing team receives notification of a positive case. When a staff member tests positive, she communicates directly with the individual to identify and notify close contacts. If the case is a student, she confirms their test results with a guardian before proceeding.

“It’s a tough job. If I get a positive case and I have 15 close contacts, that’s 20 minutes a call. If I have English as a second language families that I have to communicate with, I have to use the language line, and it’s very time consuming,” Bisard said.

When she gets a report of a positive student case, Bisard records it in a spreadsheet that the districtwide contact tracing team can access. All of the student’s teachers receive an email asking them to report the infected student’s close contacts. Whoever teachers identify will then be required to quarantine for 10 days, unless they are fully vaccinated.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a close contact must be within six feet of a positive case for a cumulative total of 15 minutes or more over a period of 24 hours. For students in K-12 schools though, this definition excludes people between three and six feet from each other as long as both are wearing masks correctly.

“I think the CDC recognized that students need to be at school, so they made an exception for classroom settings,” Roark said. “That exception is only good if both parties are wearing masks. So it’s an additional incentive from the CDC for schools to mandate masks.”

The district contact tracing team uses the spreadsheet to call the guardians of positive cases, convey quarantine directions and determine close contacts.

Until Sept. 13, when the tracing process became more centralized, Bisard was primarily responsible for communicating with the families of positive students and close contacts at CSHS. She says her normal work day lasted from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., but she was going home at 6 p.m. After dinner she addressed emails and phone calls into the evening.

“This is my priority here: the clinic. I may get notifications in, but I’m dealing with students with daily medications and chronic illnesses and emergencies,” Bisard said before the changes in the notification process were implemented. “Sometimes I don’t get those notifications until the end of the day.”

Now 12 new hires assist in contact tracing districtwide. Ten are a mix of undergraduate and graduate students in UGA’s College of Public Health, and the other two are clinical assistants to share the workload with existing school nurses at Cedar Shoals and Clarke Central high schools.

“By supplementally staffing our district contact tracing team, we can do a lot more in the high schools. We can make sure that teachers are notified every time they have a positive case in their classroom,” Roark said. “We can offer a direct line of communication for teachers to report directly to the contact tracers any close contacts that may have been in that classroom, just trying to kind of cut some of the work off of the plate of the school nurse and redirect it to the district contact tracing team.”

Roark found the UGA students to join the team when Bagwell Adams reached out to check on CCSD.

“I think the real hero here is Amy Roark. I find her to be an incredibly competent, compassionate, hard working person who is approaching the problem of the pandemic in a public school system in the best evidence-based approach she can,” Bagwell Adams said. “I think that she has been extraordinary under lots of stress.”

Despite the new help, Bisard says the nature of high school continues to challenge her and the teams’ exhaustive contact tracing efforts. For example, students are responsible for identifying their own close contacts outside of classroom settings. In order to determine who goes into precautionary quarantine, positive students have to know and remember the names of others at their lunch table, of those they walked in the halls with and peers from any other context that may have resulted in close contact.

“Because students are with so many kids at the same time, a lot of kids don’t know the full names of the people they are around. I may not be able to contact trace the people they sit with at lunch,” Bisard said. “There’s so many people in the building at the same time, there’s just no way for me to accurately identify all close contacts the way I would like to. I just can’t.”

She says contact tracing on buses mimics classrooms. Drivers are asked to enforce seating charts to help determine close contacts later.

“If there is a positive case, I’ll notify transportation, and with the student ID number transportation can go back for that bus number, look at the video and determine who was sitting in that seat based on their seating charts,” Bisard said.

CSHS teacher and district bus driver Brian Heredia says masks are difficult to enforce on buses. In the mornings masking is less of an issue, he says, but some students neglect their masks in the afternoons.

“The weather tends to vary and the temperatures get hot on the bus sometimes, and it makes it harder to breathe through the mask,” Heredia said. “So I have students that will not wear their masks. I understand it’s hot, but masking is one of the most effective tools for making sure that the spread of COVID is prevented.”

Additionally, he says while seating charts exist for the bus routes, sometimes drivers cannot implement them.

“We have the seating chart, but the number of students that we have on our bus varies widely depending on the day. It’s not always the most effective tool, especially when we have other drivers subbing for routes. There’s no way we can control that because we don’t have that information,” Heredia said.

He says when a student tests positive on his route, he receives notification of a positive case but not of the student’s name or where they were sitting.

“I’m honestly a little bit concerned about it, but at the same time, I just have to keep doing my job. Kids need to get to school, and so that’s what I do,” Heredia said.

Used in combination with masks, seating charts and social distancing, surveillance testing is a component of contact tracing that ideally identifies asymptomatic and symptomatic cases earlier to prevent spread. In Atlanta Public Schools staff are required and students have the option to participate in surveillance testing. Twice weekly, staff take a rapid antigen test for COVID-19, and students who opt in take tests on Mondays.

“In order for us to control the spread of the virus, we have to have both tracing and testing,” Bagwell Adams said. “Typically we need testing that gets us results back pretty quickly, within 24 to 48 hours, because that’s critical. In a best case scenario we would be doing surveillance testing.”

Bagwell Adams says the best practice for surveillance testing is taking random samples of the student body to take saliva-based COVID-19 tests. Then students who test positive and their close contacts would quarantine.

Roark says she is pursuing rapid testing on site in CCSD schools, and the district could partner with the Department of Public Health or a private company to provide a “turnkey testing service.”

“You really need different types of tests for symptomatic testing versus asymptomatic testing so thinking about how to do both is really what I’m interested in,” Roark said. “I’m really interested in a test to stay, test to play mentality, which is where kids who are exposed to COVID can test to stay in school and not have to quarantine.”

From November 2020 to March 2021, the Utah Department of Public Health implemented “Test to Stay” and “Test to Play” testing practices in high schools. Upon school outbreaks students opt to get tested to stay in school, or they quarantine for 10 days if they choose not to get tested. Throughout the year students were also required to take a test every 14 days if they wanted to participate in extracurricular activities.

However, surveillance testing in schools requires parental consent and rapid turnaround on lab results. Delays in test results pose tracing challenges as positive cases continue to interact with their peers until the test result is reported.

“There is a lot that goes into the testing piece that sounds easier than it is unfortunately,” Roark said.

Vaccination against COVID-19 also increases the effectiveness of contact tracing as it limits spread of the virus. Additionally, in CCSD vaccinated students are not considered close contacts. Bisard accesses student vaccination records through the Georgia Registry of Immunization Transactions and Services (GRITS).

With roughly one fifth of Clarke County students vaccinated, Roark says she can only organize vaccination events when turnout is guaranteed.

“Our public health colleagues in the community are overworked right now, and in a lot of ways probably under-resourced. So for them to come into the schools and do a big vaccine clinic — they definitely want to do that — but only if we have people who are going to show up and want the vaccine,” Roark said.

On the week of Oct. 18, CSHS and Clarke Central High School each hosted one vaccine drive for students and one for staff. The staff drives also supplied booster shots. CCSD partnered with Georgia Family Connections and Innovative Healthcare Institute to run these events and to provide information sessions at each of the high schools the week before the drives.

CCSD partnered with DPH to supply vaccines to teachers and students at Burney Harris Middle School and Coile Middle School during the week of Sept. 4.

Starting Sept. 3, Athens-Clarke County government began offering a $100 gift card to people who schedule their first shot. They can collect a second $100 gift card upon receiving their second shot. At the high school drives, students received a $100 gift card and entered a drawing for a $500 scholarship upon getting their shot.

As of Oct. 15, 45% of Athens Clarke-County was fully vaccinated. On Oct. 19, the seven day case rate per 100,000 was 98.96. There were 307 total cases in CCSD and 37 in CSHS in September, and so far in October there have been 58 cases in CCSD and less than 10 at CSHS.

In August 2021, CCSD rolled out a COVID-19 case and quarantine tracking dashboard. Bisard and the other contact tracers update the dashboard whenever they confirm a positive case. The dashboard shows total cases among staff and students for the past 30 and seven days, as well as the current percentage of staff and students in precautionary quarantines. Data is provided for individual schools as well as the district totals.

While these efforts have certainly prevented further spread of the virus, CCSD high schools moved to online instruction from Sept. 7-11 as part of a 10-day pause of in-person school. On Sept. 4, 6.4% of CCSD and 4.9% of CSHS students and staff were in precautionary quarantines. Senior La’Kayla Massey was one of the students isolating for COVID-19 that week. She had already spent a week of August in a precautionary quarantine.

“School, softball, paid internship, while also trying to apply for colleges and meet deadlines, this is one of my hardest years,” Massey said.

Isolating through the week of online learning, Massey fell behind in her work while quarantining and later skipped two days of a paid internship to catch up. She says new instructional methods should parallel contact tracing and student quarantines.

“We definitely need a virtual option at all times. If a kid randomly gets sick, have a Zoom up and ready so kids can unmute themselves or leave a question in the chat,” Massey wrote in a text while she was sick because she could not have conversations without coughing. “But I also have to say that now that I have COVID-19 I’ve been focusing on trying to get rid of it, not about what my grade looks like in my class. It literally hurts for me to look at my computer screen.”