School Board votes down sending vaccine mandate out for public comment

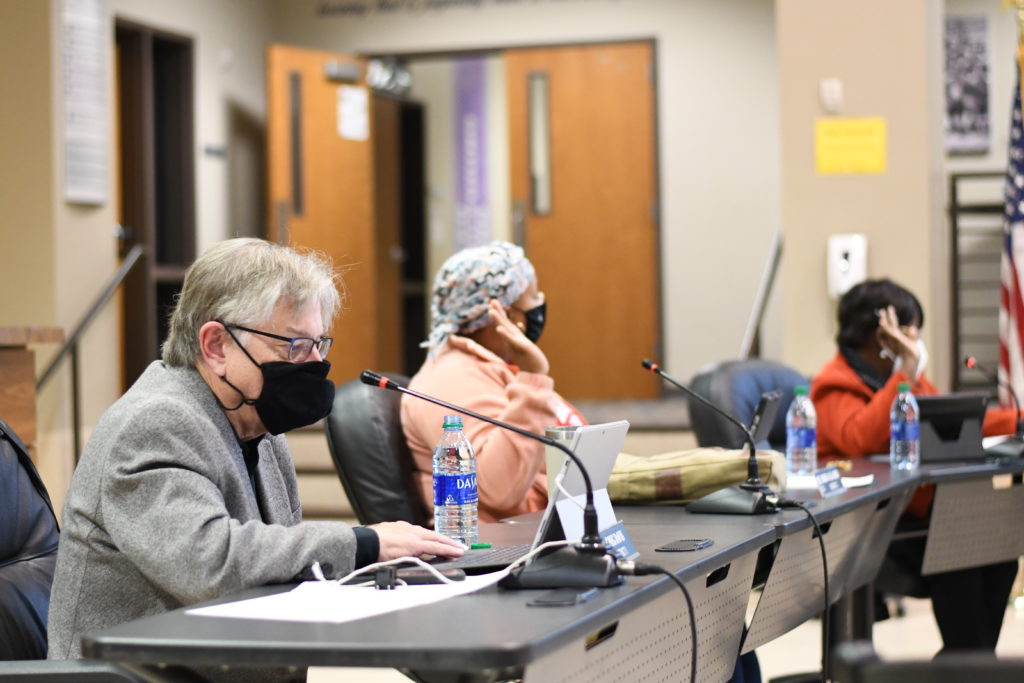

On Oct. 14, the Clarke County School Board voted not to send an employee COVID-19 vaccine mandate out for public comment. Board members Greg Davis (District 1), Dr. Kara Dyckman (District 5), Dr. Tawana Mattox (District 9) and Dr. Patricia Yager (District 4) voted yes, while Linda Davis (District 3), Dr. Lakeisha Gantt (District 7), Nicole Hull (District 8) and Kirrena Gallagher (District 2) voted no. Dr. Mumbi Anderson (District 6) abstained from voting.

Greg Davis first proposed the vaccination mandate in early October as a way to vaccinate an estimated 700 unvaccinated CCSD employees at the time.

“My intent was to put forward a policy to the entire Board that would have the best chance of making sure the schools were kept open in the second semester,” Greg Davis said.

After the policy committee, which consists of Yager, Davis and Hull, revised drafts, they sent them to Michael Pruett, the district’s legal counsel, to ensure that the mandate was legally compliant. The Board then received the finished draft.

“As a scientist, I watch these variants spin up when we don’t have vaccinated populations. It’s the reason we had the delta variant knock us off our heels in the fall, and I would really like to avoid that for January,” Yager, a tenured professor in the Marine Sciences Department at the University of Georgia, said at the Oct. 7 work session after introducing the proposed mandate to the Board.

Employees who get vaccinated would be granted two days of paid “vaccine leave” for the day of and after their vaccination. Before the mandate was revised, there was a medical and religious exemption which was later redacted because any employee could withhold from getting the vaccine. Due to the primary focus of the mandate shifting toward testing, Greg Davis and Yager referred to the vaccine mandate as more of a “testing mandate.”

Those exempted would have to get tested for COVID-19 once a week. These routine tests, if covered by the district, would cost an estimated $52 per test, and with approximately 700 employees required to adhere before the proposal stalled, COVID-19 testing would cost around $36,400 per week.

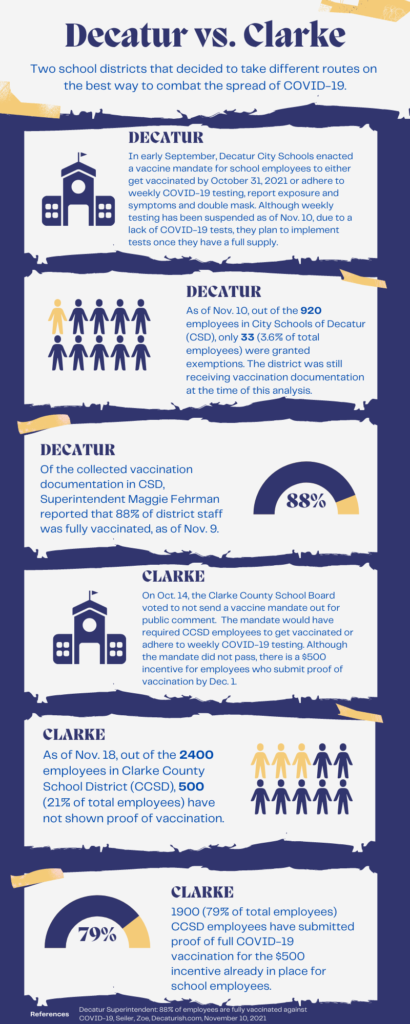

An additional approximately 200 vaccination submissions are being processed since the mandate was voted down for public comment, reducing the number of unvaccinated CCSD employees to about 500, according to information provided on Nov. 18 by CCSD Chief Human Resources Officer Dr. Selena Blankenship.

Yager pointed to leftover money from the district’s $500 incentive program to cover the cost of the testing. The district has used 71% ($850,500) of the $1.2 million set aside for the program, leaving about $350,000.

“As soon as people started talking about costs, I was like ‘Well, we were not spending that $500 that we’ve already approved, so even at the gold standard $50 a test, that’s 10 weeks. That’s almost a full semester,’” Yager said.

Greg Davis had envisioned that those required to get tested would do so on their own accord, alleviating cost from the district.

“I’ve gotten many COVID tests and I haven’t paid a dime because it’s covered by insurance,” Greg Davis said. “They have drive-ins that are open. There are drugstores. I think it’s doable. I didn’t think that we had to put it on the school district to do it.”

The mandate did not specify the operations of how tests would be administered, nor did it have to since that decision is left to Superintendent Dr. Xernona Thomas. Regardless, some Board members had concerns about these options.

Anderson, a clinical assistant professor at UGA who has a master’s degree in public health, raised concerns that implementing routine testing could further burden staff members with finding testing and waiting on the results. She also fears it could push already scarce employees in key operational roles away from their jobs.

“I do not believe that it (the mandate) would have served its purpose of keeping schools open. We already are at the brink of not having enough bus drivers to get to school. Students are having to wait an hour, sometimes two hours for bus drivers to do multiple routes,” Anderson said. “I do not want our Board to be the reason why students who do not have access to their own private transportation cannot get to school.”

Anderson recognized the negatives of placing weekly testing on the individual, as it might cause a problem for those that do not have transportation, time or ability to pay for their testing.

“99% of the testing sites are open from 8:30 to 4:30. There is one testing site in the entire county that’s open until 7:30, and that’s urgent care (which) needs to be paid out of pocket if you do not have insurance,” Anderson said. “What we are saying now to these individuals is you are now incurring your own time and your own personal finances, and both of those are a cost.”

Though Yager agrees that lack of staff is an issue, she feels that a testing mandate would reduce the number of quarantines that keep staff out of work.

“The reason we went online when we did was because we didn’t have enough staff. Teachers were having to go home and quarantine, or they were sick, or bus drivers were calling — just all the quarantining that was happening,” Yager said.

Although the Board is at odds as to the best way to go about this issue, the discussion could still come back to the table. Those who wish to bring the mandate back for discussion would have to submit a new policy to the policy committee by Nov. 25 to be considered in the Jan. 13 Board meeting.

“What I would have liked to have seen brought to the floor prior to us implementing a policy that would cost the district nearly $36,400 (the testing cost for 700 employees) a week, is taking half of those funds and increasing the $500 vaccine incentive, and strategically doing it where the vaccine incentive was increased for all staff through the holidays,” Anderson said.

Innovative Health Institute owner Dr. Cshanyse Allen has coordinated vaccination drives at Clarke County schools. She says that for vaccination rates in Clarke County to go up, people need to feel heard and informed about what getting vaccinated will do for them and their community.

“A testing mandate is not going to lead to more vaccinations if you’re not educating them,” Allen said. “You have to plan and you have to be serious about what you’re doing and have educational sessions or have a section in there where you’re educating them about it, give them good information about COVID-19, and try to dispel the myths. That’s what we did at both high schools.”

After a month of hearing public comment, the mandate still could have been revised, leading Yager and Greg Davis to be disappointed that the mandate did not pass.

“In the seven years I’ve been on the Board, I’ve never seen the Board appeal a policy before it went out for public comment,” Greg Davis said. “That’s how we kind of gauge things because we’re only nine people.”

COVID-19 vaccine mandates are becoming more common. Atlanta cities Decatur and Brookhaven now require employees like police officers and firefighters to get vaccinated against COVID-19 or adhere to regular testing. Recently, UGA became one of several Georgia public universities that will begin mandating vaccines for federal contract employees.

On Sept. 7, the Athens-Clarke County Commission passed a vaccine mandate for county employees. The mandate, which included several incentives for employees who showed proof of vaccination by the required date of Nov. 10, currently has no form of “progressive discipline” for those who do not comply.

Since the implementation of the mandate, 1,183 ACC employees submitted their proof of vaccination and 34 employees requested exemption out of 2,044 full and part time county employees, translating to a 57.9% vaccination rate for ACC employees. A total of 55 employees (2.7% of total county employees) separated from employment during this time, six of which are retirees.

Athens-Clarke County Commissioner Russell Edwards (District 7), who proposed the Athens city employee mandate, did not have much confidence it would result in overwhelming vaccination outcomes. Rather he felt that it was the first step towards enacting more “progressive discipline” mandates in the future.

“There’s a lot of fear out there. What’s interesting though is we’ve seen that mandates have been successful and employees who claimed that they’re going to quit in large numbers do not, and they actually end up complying. The New York Police Department, they had a mandate, and over 10,000 officers got vaccinated and 34 finally went on, resigned or went on unpaid leave. So a tiny fraction ended up following through with the threat of quitting,” Edwards said.

Anderson notes that vaccine mandate compliance depends partly on where — and how — it gets implemented.

“Mandates tend to increase compliance, but the level to which they increase compliance is really dependent on the community’s level of trust,” Anderson said. “Now the true reckoning is, ‘How much do we now continue to force philosophies and motives and actions on those individuals without first working and collaborating with those individuals and addressing their issues of trust, and addressing the issues of historical injustices?’” Anderson said.