Conversations regarding Critical Race Theory arise in Clarke County School District

Following the release of the Georgia Board of Education’s resolution condemning classroom discussions about systemic racism, the term “Critical Race Theory,” or CRT, has been used left and right in the media.

While the resolution did not explicitly mention CRT, it expressed anti-CRT sentiments. Governor Brian Kemp reaffirmed this opposition to CRT in a letter to his Board of Education, in which he stands by their conclusion on systemic racism in school and deems CRT “divisive and anti-American.”

This letter sparked arguments over whether CRT should be discussed or taught in schools nationwide and what CRT actually is.

“Most (teachers) don’t teach it, but we absolutely should,” said Lora Smothers, founder and director of Joy Village School, a new K-8 school opening in the Athens area next year. “Encouraging (people) to see the world through the lens of race and how it impacts all of our systems is a great thing to do.”

What is Critical Race Theory?

CRT became a widely recognized term in 1989 after being introduced by American lawyer, civil rights activist and philosopher Kimberlé Crenshaw. The theory consolidates research by scholars, lawyers and activists seeking to deepen the understanding of how race is embedded into American society. It concludes that racism is not confined to individual people and their beliefs or behaviors, but that those beliefs and behaviors are subconsciously motivated by the racism that is ingrained in American legal systems and institutions.

CRT emphasizes that racism is a social construct rather than an issue pertaining only to individuals. Despite CRT and the resolution being opposed politically, the resolution also expresses that racism is not the fault of any one individual. It states, “We, the State Board of Education for the State of Georgia … Believes that no state education agency, school district or school shall teach, instruct, or train any administrator, teacher, staff member or employee to adopt or believe any of the following concepts: (a) one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex; (b) an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.”

While it seems that CRT and the resolution may agree on this idea, that middle ground ends when it comes to the perception of racism in the United States.

CRT poses the idea that racism is embedded in America’s social and legal systems and that singular racist incidents are “manifestations of structural and systemic racism,” as civil rights attorney Janel Georgia describes in her article “A Lesson on Critical Race Theory.”

In contrast, the Board of Education’s resolution states, “We, the State Board of Education for the State of Georgia; 1. Believes the United States of America is not a racist country, and that the state of Georgia is not a racist state …”

Although the resolution states that America is not a racist country, Christina Willis, senior at Cedar Shoals, believes that racism is a prominent part of this country’s history.

“If we were to exclude race from everything, a lot of American history wouldn’t have happened, like the Jim Crow laws and the Japanese internment camps,” Willis said.“I think (schools) should teach it. I would love to know what Critical Race Theory is.”

Should CRT be discussed in schools?

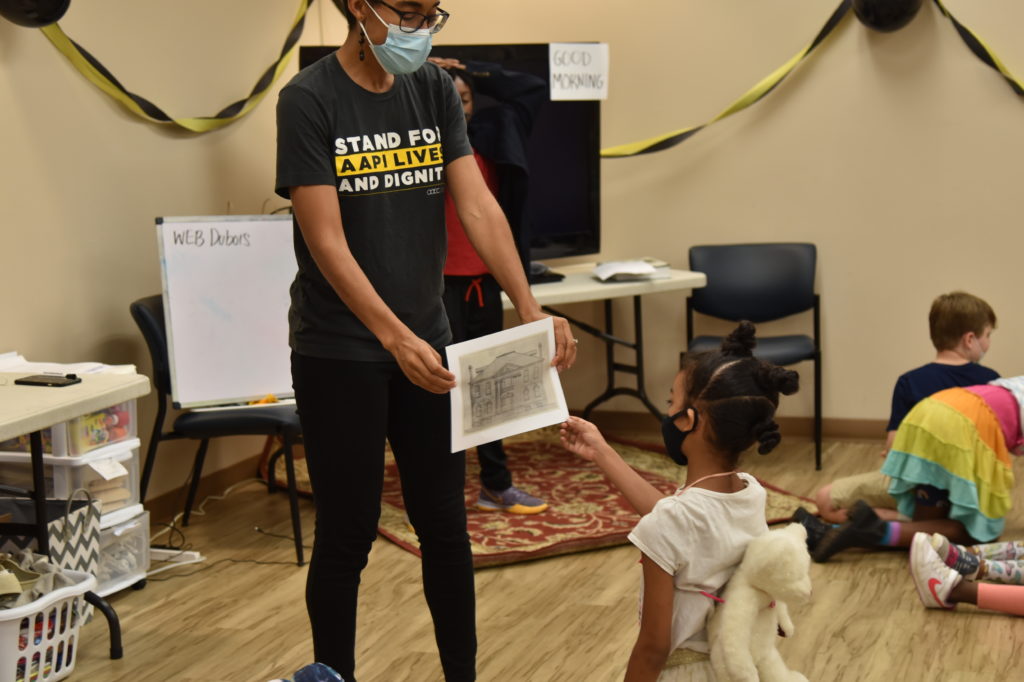

The Athens Anti-Discrimination Movement (AADM) believes that it is important to combat the attacks against CRT by introducing conversations about systemic racism in the classroom, as demonstrated by their free public education series Teach the Truth Thursdays. The series aims to support educators in teaching students about systemic racism, oppression and overlooked civil rights movements. Every Thursday the organization meets at AADM’s Justice Center for a free dinner followed by a session facilitated by a community educational leader about a skill or subject that could support teaching truth in classrooms. Participants can also access the meetings online.

“Because I wasn’t taught the full truth about our nation’s history in my AP American History class at Clarke Central High School, I didn’t know that there is a racial caste system in this country,” said Chaplain Cole Knapper in her opening speech during a T3 Thursdays meeting. “Because I didn’t learn that, I experienced racism, prejudice and discrimination that I was ill-prepared for when it happened to me in my life.”

Social studies teacher Montu Miller also believes hard conversations pertaining to race are necessary for fostering a society with fewer racial tensions.

“The reason we’re having these conversations in 2021 is because we did not have them in the early 1900s,” Miller said.

Smothers also wants children to understand that we live in a country where racism is still present within our institutions.

“Children should be mindful of (racism) because if they’re not encouraged to be mindful of it, they’re going to be living in a fantasy where it doesn’t exist,” Smothers said. “It means that a little boy or girl who’s never encouraged to think about it grows up to be an adult who is your senator, your pastor, your banker or your doctor. There are real-world consequences of not knowing how we exist in this space together.”

What does it look like to implement CRT in schools?

Introducing CRT and discussing systemic racism in classrooms looks like a peer leadership class, or educating students about Athens’s own Linnentown. It even looks like a school dedicated to centering the joy and thriving of Black students in a society where they are often discriminated against by school systems, as the 2013-14 Civil Rights Data Collection shows.

Smothers’s school, Joy Village, has a mission to center the joy and thriving of Black students. The school’s curriculum will emphasize math, language arts and African-American studies, based on research by professors such as Diane Hughes and Emilie P. Smith showing that fostering knowledge of cultural and ethnic backgrounds leads to positive self-identity in children. The school is now open for enrollment for the 2022-23 school year.

“The whole idea is to teach them in a way that speaks to their black experience: their music, their knowledge about their world, their sense of place,” Smothers said. “It’s going to be all about learning cool Black history from the people who have lived it in our city and just creating a safe space.”

Former Cedar Shoals teacher Katherine Johnson, who now teaches peer leadership classes at Clarke Middle School, also believes in the importance of having difficult conversations about systemic racism in America’s institutions. Peer leadership supports students who are struggling academically by pairing them with a peer mentor. According to Johnson, this class cannot be taught without examining systemic racism.

“Because of the structures of school and society, a lot of times the students who struggle the most are Black and Hispanic boys,” Johnson said. “The reason my whole class has an exploration on race and society is because you can’t have high achieving kids mentoring kids who are low achieving unless you look at why most of them are Black and Hispanic boys.”

Johnson encourages students to share their stories, exchange their ideas and learn to be empathetic to experiences and opinions that differ from their own. These conversations focus heavily on systemic racism and its effects on students. Although Gov. Kemp’s condemnation of CRT may be an attempt to suppress these discussions, students such as Clarke Middle eighth-grader Iayah Edwards believe these conversations are important.

“Many people think that if we don’t talk about (racism), it’s magically going to disappear,” she said.

Cedar Shoals English teacher Brent Andrews opens up conversations regarding systemic racism in his classroom by including the history of Linnentown in his curriculum.

“I’ve put it on assignment sheets. When kids are writing their own rhetoric for a project, they could choose Linnentown as the thing they focus on,” Andrews said.

He aims to empower students to use their voices to speak out against injustice and explore difficult topics.

“The big thing for me is that students understand that they’re not alone in their frustrations, that people who are part of the system realize the system is broken and that (students) understand that they can not only be agents of change in themselves but that they can actually have an impact on their society,” Andrews said. “My role as a teacher is to try to repair any bit of harm that I can personally, and make up for the fact that we still have these inequalities in our country.”

Is CRT actually banned in schools?

Some states have passed legislation forbidding discussion or training of the idea that the U.S. is inherently racist and that racism is implemented structurally. An Idaho house bill signed into law explicitly mentions CRT, claiming that the tenets often found in Critical Race Theory cause further division on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color or national origin.

Despite legal action in other states, the only statement from the Georgia government regarding discussions of systemic racism is the BOE resolution, and it is just that: a resolution that is not written into law. Teachers are not legally prohibited from discussing or teaching concepts surrounding systemic racism or even discussing or teaching CRT itself.

Though not signed into law, the BOE’s resolution prompted action from local movements and educators.

Prompted by Kemp’s letter and the state board’s resolution, Amelia Wheeler, doctoral student at UGA and former economics teacher at Cedar Shoals, organized the Pledge to Teach The Truth event last August to further educate teachers and students on the resolution and encourage them to continue teaching about systemic racism. After this event, the AADM developed Teach the Truth Thursdays.

“This stunning barrage of legislation and policy aims to ban teaching CRT and supposedly divisive topics in the curriculum,” Knapper said. “But we know that the real target is the truth.”

To show support for conversations regarding racism in the classroom, The Clarke County School District BOE developed its own resolution, countering the Georgia BOE’s.

“The resolution passed by the Clarke County School Board sought to ensure teachers that we support classroom discussions on race,” said Greg Davis, District 1 school board representative for the Clarke County School District. “The point is to educate, and through the process of education, we better our society.”