“The reading wars” — a battle CCSD is willing to fight

Most don’t remember the exact moment that the act of comprehending printed words clicked. Through trial and error and many bedtime stories, children begin to read at six years old on average. These tactics of learning through free-range exploration, context clues and listening to books aloud are known as balanced literacy — a harshly debated method of teaching young students to read.

Balanced literacy — the “traditional” style of reading instruction — is known for its flexibility and holistic approach. The process is praised for the belief that it creates longevity in the child’s choice to read for recreational pleasure as kids are encouraged to read about topics they are interested in. The disconnect between the most effective way to teach children to read begins here.

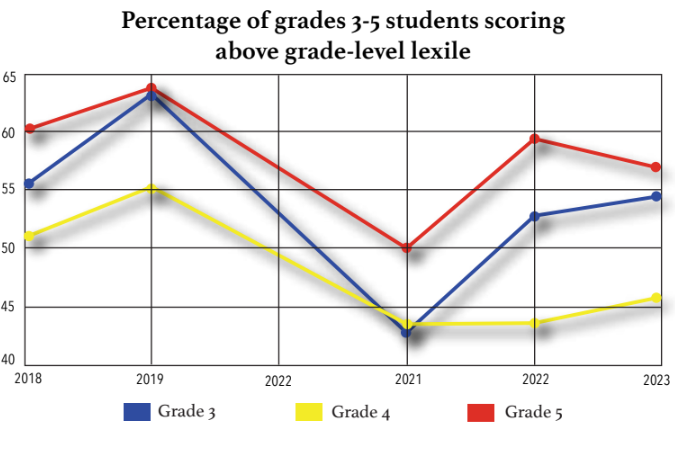

As seen from the 2022-23 Georgia Milestone American Literature and Composition End-of-Course Assessment, 54.1% of the 886 fourth grade students tested in the Clarke County School District read below their grade level. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, scores were not ideal, with 49.1% of students in the same grade reading below grade level in 2018.

CCSD’s previous curriculum, Fountas & Pinnell, claims to follow the science of reading, but has recently been under fire for its simplistic approach that some say more closely resembles balanced literacy. The program released a statement addressing what they call “misinformation” circulating about their techniques, but literacy statistics have not improved since CCSD took on this controversial curriculum.

“It’s an urgent issue across the nation, not just in Clarke County,” CCSD K-5 ELA Curriculum Coordinator Christine Havens-Hafer said. “The numbers weren’t getting better as far as literacy rates go using the former programs. They’re (CCSD) realizing something has to change; now they’re changing it.”

In a July press release, Superintendent Dr. Robbie Hooker said, “We have done a hard reset on our approach to reading and have trained our school leaders as well as 800 district teachers in a more balanced, ‘science of reading’ approach.” With the new programs, Hooker hopes to “… move the needle on student outcomes going forward.”

“The focus wasn’t as discrete (using balanced literacy) and what I mean by that is ensuring that a student gets enough of a skill before they go on to the next skill,” Havens-Hafer said. “You need to get these things in the right order, or else they don’t make sense together. How can you solve a math problem if someone didn’t teach you multiplication and division? (It) doesn’t matter if someone gives you the formula for that math problem and tells you this is how you solve it.”

Enter “structured literacy,” an ideology based on a foundation of the “big five” pillars of reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. Unlike balanced literacy, students are taught to decode words and intentionally learn the specific sounds that create them. Also known as the “science of reading,” this formulaic method is rapidly becoming the accepted norm for instruction, including within CCSD.

“Just because you can read the words on a page doesn’t mean you know what you just read. I tend to stick to the emphasis of this systematic approach; every skill builds on another skill. When there’s gaps, our students begin to struggle, and it gets worse over time. It makes reading a lot less enjoyable,” Havens-Hafer said.

Passed on April 13, 2023, House Bill 538, also known as the “Georgia Early Literacy Act,” mandates this change in reading education throughout the state. The bill emphasizes providing materials for “developmentally appropriate evidence based literacy instruction,” by incorporating both teacher training and learning resources. As a result, the Georgia Department of Education (GADOE) curriculum closely aligns with H. B. 538 and the structured reading pathway it enforces. The K-5 foundational skills and concepts listed in the GADOE standards include five objectives: phonological awareness, concepts of print, phonics, fluency and handwriting, including cursive.

To ensure the development of reading comprehension, the law instructs local school boards to “administer universal reading screeners multiple times each school year to students in kindergarten through third grade.” To conduct these screeners, CCSD has modified i-Ready, the formerly daily practice program for language arts and mathematics, into a diagnostic tool. The results of the fall, winter and spring screeners will be sent to the GADOE for analysis.

“They (CCSD) want to use it for doing some assessment in the beginning of the school year, just to figure out where kids are as far as their deficits or their strengths,” Havens-Hafer said. “It’s more like they’re just trying to get a pulse check to see if the students have improved from the last time they took one (assessment) maybe in the spring. If over the summer was there any improvement? Is their literacy growing? Are their math skills better? And then they use that to help determine instruction.”

While there are no specific materials mentioned in H. B. 538, CCSD elementary schools adopted a Wilson Language Training subprogram, Fundations, in the 2022-23 school year. The strategy applies “multisensory” techniques in daily lessons to engage students in structured reading, spelling and handwriting. Some teachers are impressed with the changes they already see in students.

“Even going into this year, there is little gap in any of their phonological awareness. It’s amazing. But older kids in third, fourth and fifth did not have this (Fundations) in the early years. They’ve learned to figure out words, but they don’t know how to decode certain kinds of things. It was really eye opening to see where kids fell through the cracks,” Whit Davis Elementary EIP teacher Karen McDonald said.

While Fundations is only meant for K-3, Wit and Wisdom, a Great Minds program, is available to students through fifth grade. This GADOE approved resource that CCSD has also implemented is intentionally designed to be interdisciplinary. Though its main focus is structured literacy, it integrates other subjects such as science and history for children to read about. The program is influenced by Scarborough’s Reading Rope — a physical demonstration of reading comprehension using pipe cleaners to show how language comprehension and word recognition intertwine to create fluent reading.

CCSD is also applying direct vocabulary instruction — the intentional navigation of words as opposed to learning indirectly through conversation or context clues. This initiative stems from a multi-exposure and frequent repetition method called Marzano’s Six Steps: describe, restate, illustrate, engage, discuss and games.

“I think we’re going to see some really different readers as they get stronger and stronger every year. The focus is a lot more comprehensive now as a district on literacy; a lot of people have their arms around this in our schools,” CCSD ELA 6-12 Curriculum Coordinator Carlyn Bland said.

These new materials are part of Tier 1 instruction — the “universal” classroom lesson taught to the majority of children. As seen from previous CCSD test scores, some students may need more support in certain areas such as reading, and may not all be suited for Tier 1.

This is where Tier 2 comes in. These lessons are taught in addition to the Tier 1 material as an intervention for struggling students. The targeted approaches, such as Heggerty Phonemic Awareness, utilize different methods for pushing children to meet their grade level goals. One of Heggerty’s main support solutions are hand motions that accompany the curriculum. The teacher shows the beginning of a word on their left hand, and the end of a word on their right, using “chopping motions” to separate the syllables. The intervention program elaborates on rhyme, onset fluency, segmenting and more throughout its guides.

Approaches like Heggerty and structured literacy as a whole are suited to help detect reading delays like dyslexia. The step-by-step process is able to identify when students are lagging and in which specific areas.

“People are in different places for different reasons at different times, including when they want to read, what they want to read, how much they want to read and in what formats they want to read. We need to meet students and readers where they’re at, and really listen to what they’re telling us,” Whit Davis Elementary Media Specialist Lauren Knowlton said.

An additional resource includes Geodes — a Tier 2 program under Great Minds in association with Wilson Language Training — emphasizing that “children are capable of reading to learn while learning to read.”

“A lot of the (Geodes) books are social studies and science based so that you are pulling in those subjects throughout reading,” Whit Davis Elementary kindergarten teacher Brittany Geithman said. “When we get our ELT time, Geodes is going to come into play to help the kids that are struggling with certain skills.”

The apparent concern nationwide is how structured literacy may impede childrens’ desire to read in the future. Those who support balanced literacy question the effects of relentless systematic instruction. Young students with short attention spans are forced to meticulously learn each individual letter, and some worry this may lead to a decline in reading for pleasure later on. Knowlton sees another side to this belief.

“There’s a different kind of reading that’s appropriate for different times and for different reasons, so I think they (structured and balanced literacy) can definitely build on each other and complement each other,” Knowlton said.

Geithman supports the methodical design of the new programs, and thinks they will actually encourage reading as students get older. She notes that without the ability to read fluently, there is no motivation to pick up a book; the struggle overpowers the desire.

“Why would you want to read if you’re spending all your time trying to decode a word in the sentence and don’t have the fluency or comprehension? If you’re not comprehending what you’re reading, then there’s no point in it anyway,” Geithman said. “They then become more of a lifelong reader because they feel more confident in their skills.”

As she teaches, Geithman employs three different strategies she believes are necessary for comprehension: phonics, background and interest. Structured literacy covers phonemic instruction, whereas background and interest follow a more balanced approach to provide context before, during and after reading.

“They have to have phonics because if they don’t know how to decode a word, then when they get into the upper grades, they’re not gonna know how to pull out the chunks of a word or have the necessary skills. You want them to be able to read things that interest them, and you want to give them that background knowledge if they come into class and don’t have a lot of experience,” Geithman said. “ I think the best way to teach is to incorporate all of them together.”

The contrasting perspectives of teaching children to read in the most effective way have created a divide in schools. The balanced, holistic method aims to preserve the desire to read, as well as provide context during the development of skills. The structured science of reading promotes a formulaic design, making sure to guide students through each step. Some believe the two approaches can coexist, creating a stable progression of comprehension. Ultimately, the end goal of improving literacy remains the same.

“Everything you do is based on your ability to read; it’s very difficult to get by in life if you are illiterate. The power of literacy and reading is beyond words,” Knowlton said.