A disengaged democracy: why teen voting still lags behind

A recent Gallup poll showed that over 70% of Americans put “a lot of thought” towards this year’s election. However, that still leaves millions of eligible voters who are not engaged or interested in civics.

Young voters have always been the demographic that votes the least, typically voting 15-20% below the national average according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Voters under 24 years old haven’t voted above 50% since 1968, yet no other demographic has gone below 50% since the Census Bureau started recording demographic data in 1960.

Most candidates tend to be older and represent older interests, causing some teens to feel ignored. The average age of Congress members has increased by ten years since 1981, making the House of Representatives one of the oldest legislative bodies in the world.

“Our laws are skewed toward benefiting the oldest in our society, and it’s because young people aren’t showing up to vote,” Cedar Shoals social studies teacher Jesse Evans said.

Teens are more diverse as a demographic, making them harder to appeal to than the more monolithic older generations. Around 15% of those under 24 identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community, compared to 5% of adults. Teens also show a wider ideological gap between men and women. 71% of young women vote with the Democratic Party, while only 53% of young men do. There is also a large rift between young urban and rural voters, with 28% of young urban voters being conservative and 64% of young rural voters.

And then there’s school. Many teens just have busy lives and don’t focus much on politics. Many of the seniors who are eligible to vote this year are juggling AP classes, dual enrollment, extracurriculars, responsibilities at home, jobs, college applications and other schedule conflicts, lacking time to watch interviews and research policy positions.

“I don’t really know much about the people, so I feel like to vote I’d have to be into it, or want to do research,” Cedar senior Nicole Estrada said.

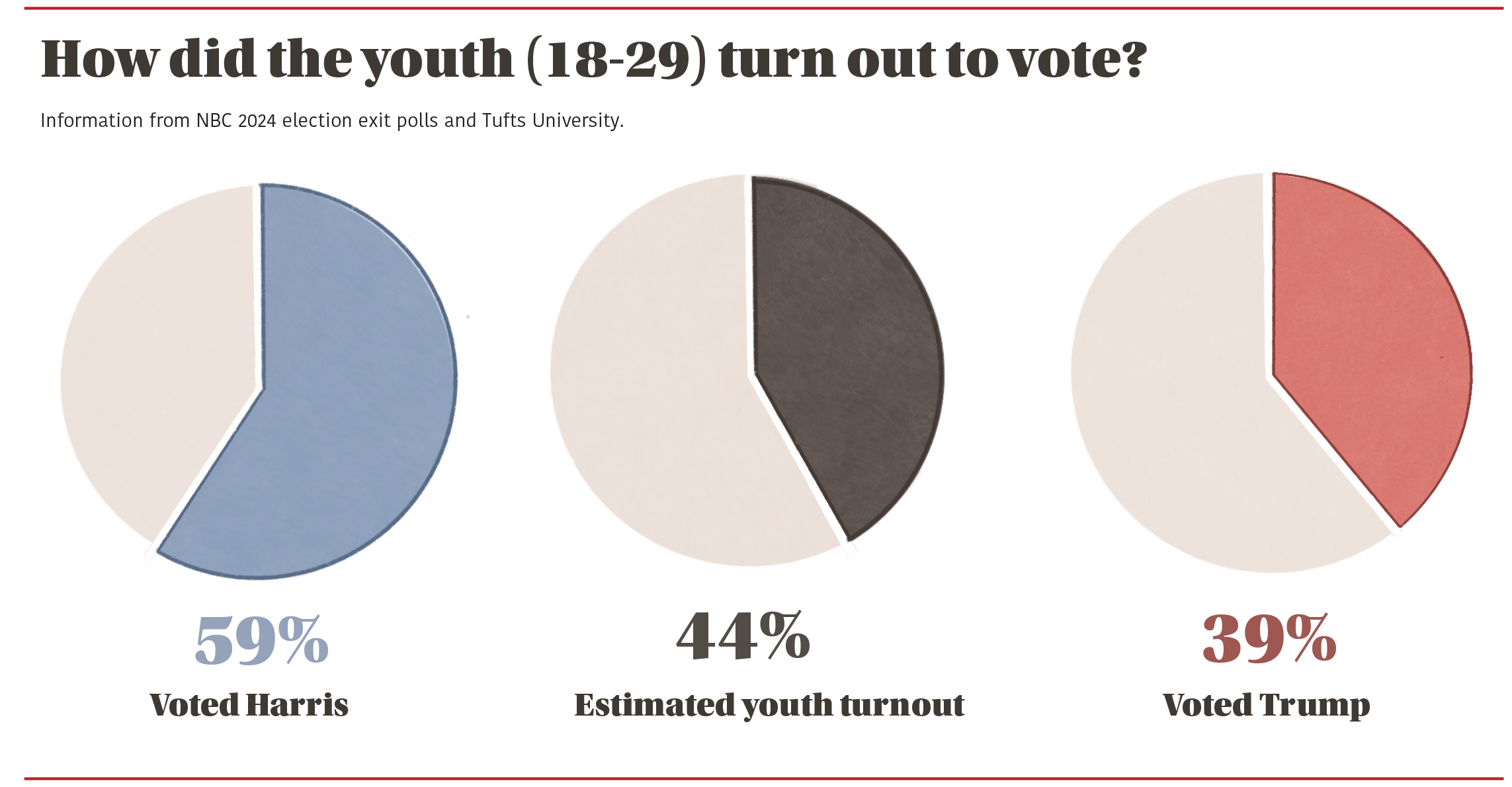

But youth are beginning to get more involved. Starting in 2004, youth have voted significantly more than usual in presidential elections. In 2020, they posted their highest voting rate in 50 years. In the 2024 presidential election, around 44% of young people voted according to Tufts University.

“People are getting involved, and I think it has a lot to do with people not being comfortable or disagreeing with a lot of what’s going on in the political world,” Clarke County Director of Elections and Voter Registration Charlotte Sosebee said.

As youth grow as a voting bloc, they’re also gaining greater representation. Maxwell Frost recently became the first Gen-Z congress member at age 26. Many other Gen-Z candidates ran for Congress this year, including Cheyenne Hunt of California, Bo Hines of North Carolina, Joe Vogel of Maryland and several others.

Low voter turnout might be due in part to low awareness of the election. According to Evans, teens may not know how to register or vote because of the lack of education available.

“There’s been a lack of high quality government, civics and political education. When I graduated high school and went to college, I started learning things that I should have known before then. Everybody should know the things that I was learning. If we’re going to have a government that really serves the people, the people need to know how the government works,” Evans said.

One solution Evans suggests is moving American Government class to junior year to keep politics fresh in the minds of new voters. He also thinks civic education should be incorporated into every grade level, beginning in elementary school. He has organized election field trips to take seniors to the polls, most recently on Oct. 30.

“We should be teaching government and civics in every year of school, from pre-k all the way through 12th grade. We should be doing everything we can to help educate our young people,” Evans said.

Senior Amarya Herndon, who voted this November, wants election advocates to take a more hands-on approach to providing voting education.

“You have to come to them and tell them to vote. Come to them face-to-face,” Herndon said.

Many advocates have pointed to a lowered voting age as a possible solution to decreased engagement. Argentina, Brazil, Austria, Cuba and many other countries have reduced their voting age to 16.

Starting in 2013, five cities in Maryland lowered their voting age to 16, with impressive results. 16 and 17-year-olds voted at higher rates than 18 to 24-year olds, and they also continued to vote at higher levels as they grew up.

“They (16 year olds) have been involved in all of the campaigns of those candidates. The conversations that they’re having amongst themselves seem to be pretty well educated. I don’t see that there would be a problem for 16 year olds voting. I believe they would have enough information to vote, and they would be able to use the systems that we have in place,” Sosebee said.

Lowering the voting age would also align more closely with the civic education teens receive in freshman year U.S. government and politics, though this is not a freshman class in every school in Georgia.

“I think that it (lowering the voting age) would be a motivator for the states and communities across the country to really take political, government and civics education more seriously and prioritize it,” Evans said.

Some experts have said that the average 16-year-old’s brain isn’t developed enough to make decisions adequately, although research on this type of decision-making is inconclusive. Another argument made is that teens may just reflect their parent’s views since most still live at home.

Junior Heily Vazquez disagrees with the push for a younger voting age.

“It’s not a good idea due to everything that’s going on in society right now. I feel like we should keep it at 18. A 16-year old is still in high school and hasn’t finished comprehending what they want in life,” said Vazquez.

Herndon had a positive view of lowered voting age.

“I think teenagers would have more power to speak their opinion, what they think and what’s going on in their life,” Herndon said.

Compulsory voting, sometimes referred to as mandatory voting, offers a more drastic solution for the low turnout. Compulsory voting policies typically require all citizens to vote in elections, often with exemptions for religious objections and health issues.

Twenty-seven countries currently have compulsory voting policies, including Turkey, Egypt, Australia, Brazil and Mexico. They have 7% higher voter turnout on average than non-compulsory countries. A study by the Harvard School of Government has shown that 78% of new voters brought in by compulsory voting policies in Australia supported the liberal candidates, suggesting that compulsory voting moves election results to the left.

Research has shown that requiring citizens to vote moves the voting demographics closer to the country’s actual population demographics. It can also make voting easier and more accessible. Some people may choose to do more research since they are required to vote.

“Another aspect is making sure that our government actually reflects the values and the will of the people. I think our government would be closer to that ideal if we had the maximum number of voters,” Evans said.

It is hard to prove that these policies would meaningfully increase voter engagement. When compulsory voting was implemented in Austria, they saw a temporary boost of 3.5% that fell back to previous levels after a few years. The sudden increase of uneducated or apathetic voters could drown out those who carefully researched their candidates.

Focus on voter engagement, particularly youth voting, is increasing. However, there is still much to be done to engage and educate our youngest demographic.

“If young people want our society to be more in line with their values, they should run for office, they should work on political campaigns, they should register to vote and they should be engaged,” said Evans.