Stories under siege: How the resurgence of book banning effects education

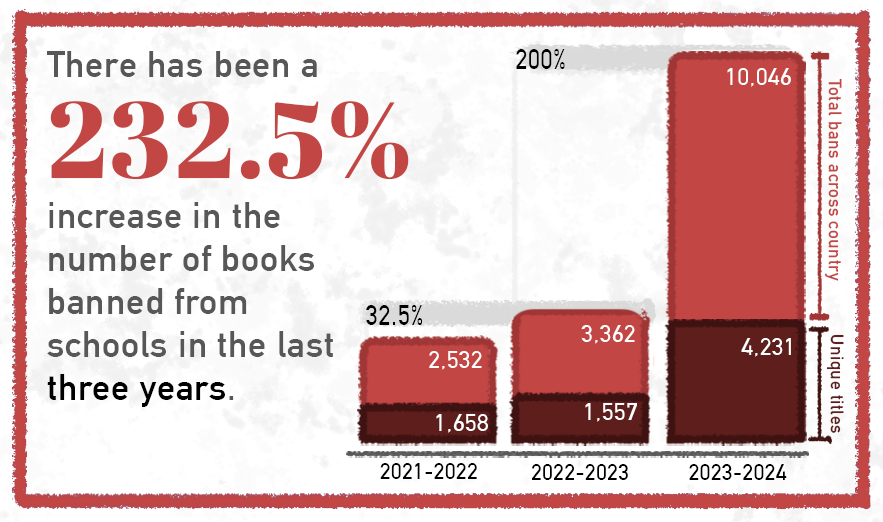

According to PEN America, nearly 16,000 books have been banned in public schools across the United States in the past five years. This is an unprecedented number since the Red Scare, a time in American history where fears of communism fueled censorship of an estimated 30,000 books.

Now, instead of political ideologies, it’s the stories of the people that are under disguised attack: especially those of marginalized communities.

According to the PEN America, there were 10,046 instances of book bans nationwide in the 2023-2024 school year, a nearly tripled increase from 3,362 instances the previous year. A significant portion of targeted books mentioned people of color and LGBTQIA+ identities. From the 1,091 most commonly banned books, 44% featured people of color and 39% included LGBTQIA+ individuals.

The trend isn’t just limited to novels. Picture books, which make up 2% of all banned titles, have been included in the list. Nearly 64% of banned picture books feature LGBTQ+ characters or themes. Similarly, 44% of banned history and biography titles focus on people of color.

According to Pew Research Center, diverse cultural representation in books is proven to help curb prejudiced beliefs in readers. In turn, censoring books that represent marginalized communities hold the possibility to make prejudice more prevalent in society.

Junior Kyron Richardson envisions that impact firsthand, and believes that removing such stories can limit valuable opportunities for understanding.

“You hear about experiences of like racial prejudice, but if you’ve never experienced it yourself, books like that put you in the shoes of somebody who’s been through it, even if it’s fictional. You get to really analyze how things like that affected that person and how it changed that person in that type of society. Things like that are the reason why we should be able to read the types of books that are getting banned.” said Richardson.

Brent Andrews has taught English at Cedar Shoals for 24 years. Although not required for the class, Andrews, along with many Advanced Placement Language and Composition teachers across the country, structures Unit 3 (Perspectives & How Arguments Relate) and Unit 4 (Rhetorical Analysis) around banned books and the climate surrounding them.

“You would think that it’s a thing of the past as we’ve evolved through society, and we’ve learned the importance of education. But that’s actually not the case. It’s increasing in its number, and the ease with which to get a book banned is also increasing through Georgia state laws,” Andrews said.

Passed in 2022, Georgia House Bill 1084 introduced the idea of “divisive concepts”: which includes nine ideas related to race and racism deemed too controversial to teach in schools. While the concepts are broadly defined, some concepts the law prohibits teaching are that one race is inherently superior to another or that the United States is fundamentally racist. The bill’s implementation has raised concerns about its impact on how race and history can be discussed in schools.

“Books are banned if they portray America as a racist society, or if they make kids feel bad about their own race. That language is coming through in laws like the divisive concept bills. We have a law in Georgia that was passed that basically says you’re not allowed to present material, which suggests that America or Georgia is racist, or that there is racism in those societies. As an English teacher and an avid student and lover of history, I would feel like a fraud if I were to teach my students that those things have vanished from our society,” said Andrews.

Books that discuss topics such as race, gender, sexuality and history appear to be banned more frequently than others. Junior and AP Language student Caroline Perry believes those stories should be amplified instead.

“I think those topics are very important for people to learn about, because they’re taboo in our society. I think that if we normalize reading and talking about topics like that, we’ll get more comfortable talking about it in our society, and we’ll be able to come up with more solutions to those problems,” Perry said.

Books are banned for a variety of different reasons, such as being ‘too graphic’ or ‘too explicit’. However, Richardson offers a deeper perspective, suggesting that some bans may disproportionately affect stories representing marginalized communities.

“I feel like book banning is only justifiable in extreme cases of books promoting negative aspects of life. I feel like the government is targeting books that tell stories about minorities, which (aren’t the real) threat to me. But let’s say there was a book teaching you how to make a bomb, and you know, things like that are actually a threat towards America. I just feel like the government is trying to focus on things that are somewhat politically irrelevant,” Richardson said.

The next step after recognizing the problem is to fix it. Andrews thinks that by banning books, the government is avoiding addressing social issues that literature can call attention to.

“I believe that the core problem with this is that people are trying to limit these conversations because they don’t want people to know that the problem exists. They don’t want to change laws and regulations to create a society that works for the majority of people,” Andrews said. “It is irresponsible to go through our entire lives as Americans trying to pretend that we live in a society that has not harmed certain groups of people.”

English teacher Hannah Doolittle is a strong advocate for reading banned books, believing that being banned is an indicator of a valuable story.

“One of the reasons why I think it’s important to teach stories like this is to help kids see other things that people go through. Someone may be acting some type of way or be making a decision that you disagree with, but you don’t know that person’s life story,” Doolittle said. “You don’t know what they’ve lived through or experienced. I think it’s a community building exercise as well: to read stories of things that we haven’t experienced ourselves. It’s all about building empathy for each other.”

Literature has been responsible for passing down knowledge for generations, and Richardson thinks that limiting the availability of certain books allows only certain views to circulate.

“Books are a way to develop society. If you’re writing, for example, transphobic content in a book where people can read and learn about that, it just continues the whole cycle of hate throughout generations,” Richardson said.

At the heart of book banning is a fundamental question: who gets to decide what young people are exposed to? Should parents dictate what their children can and cannot read, or should students—particularly those in high school—be trusted with the agency to explore complex and challenging subjects? The debate between parental control and student rights is particularly important in today’s educational climate, where difficult conversations about race, gender, and identity can be deemed too controversial for young minds. Andrews believes that most students are not in favor of book bans, but that parents advocate more for them.

“I’ve never had a student who felt that way. It’s always been parents who didn’t want their student to read the book. That brings up the issue of, at what age do we consider the right of the individual student over the right of the parent?” Andrews said.

Junior Omnia Mansour, who is currently enrolled in Andrews’ AP Language course, has a strong stance on reading banned books because of the knowledge they can provide.

“When you’re reading, that’s the experience that other people face. I don’t understand why we need to ‘protect the youth’ if there are other people around them experiencing the same things we’re ‘protecting’ them from,” Mansour said.

According to the Clarke County School District dashboard, 86.3% of Cedar Shoals students belong to a racial minority group. Mansour feels that banning books that tell the stories of minorities in America blocks out those who may find inspiration in those stories.

“Not hearing those stories and being a minority in this school is just not something that makes sense,” Mansour said. “I feel like even if Cedar wasn’t a school that’s majority-minority, I feel like (reading banned books) is still such a beneficial experience. Then, your peers are able to empathize with your situation. Hearing it is different than reading it.”

In Doolittle’s opinion, banning books denies students the opportunity to see their own lives reflected in stories. The impact is especially significant at a diverse school like Cedar Shoals.

“It’s so important for me to help kids see each other as people and see people that are different from them as people, and to understand that just because someone does something differently than you or has a different lived experience than you, it doesn’t mean that person is wrong,” Doolittle said.

From Andrews’ perspective, high school is the perfect time to expose students to complicated social issues.

“It’s absolutely imperative that English teachers push students slightly beyond their comfort zone with the literature that they read and that we have difficult conversations about real issues in society that will be affecting real people,” Andrews said.