Increasing artificial intelligence: AI makes its way into classrooms

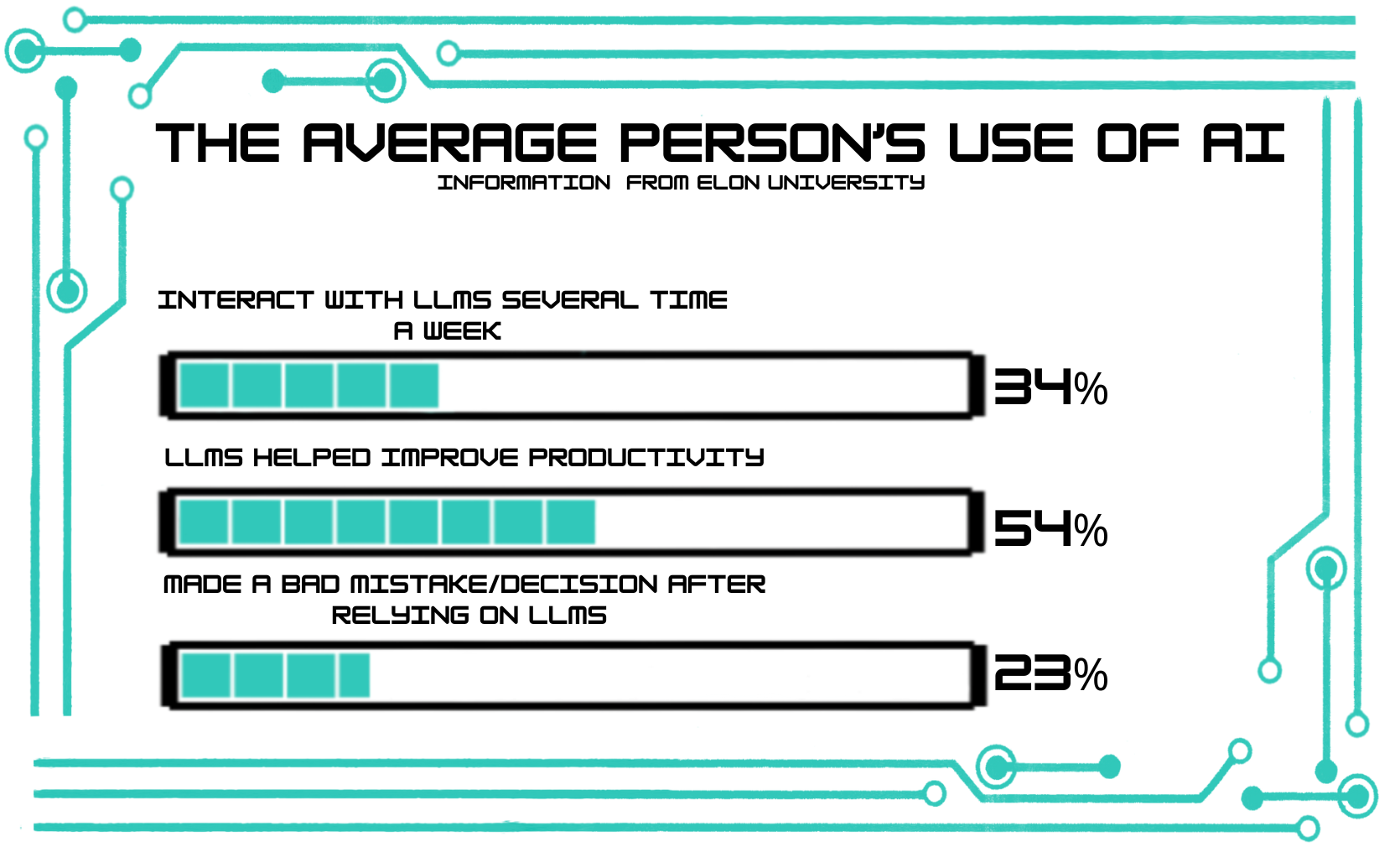

Open AI released the generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot GPT-3 in 2020, bringing the start of a rapid sweep of AI across the world. This generative technology has quickly made its way into very mainstream apps like Spotify, Snapchat and Meta apps, making it easily accessible to the average person.

GPT stands for a “generative pre-trained transformer,” a term used to describe a large language model (LLG). These machines use billions of previous inputs in order to analyze the most likely output of a prompt or situation. Following GPT-3, in 2021 OpenAI released their text-to-image AI Dall-E, and a year later ChatGPT was sent out.

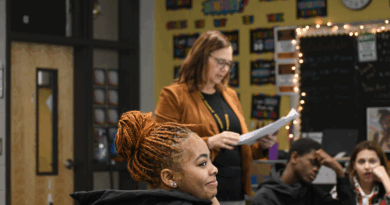

Naturally AI has also made its way into classrooms, with Google’s AI being installed on chromebooks. Students increasingly use AI not to just cheat but also to help them with learning, as a Quizlet survey reported that 89% of students use it as relating to school, with 56% summarizing information, 46% for research and 45% making study guides or materials.

In the United States, there has been a significant increase in teachers’ use of AI. Through a LinkedIn survey conducted by Education Week in February, responses showed that 60% of teachers have used AI to help them in the classroom, most commonly to create lesson plans, slideshows, study guides or rubrics.

AP World History teacher Robert Olin most often finds himself using ChatGPT or MagicSchool AI as an assistant to make assignments for students, such as asking about what to include in presentations or taking the best ideas and incorporating them into lessons.

“My goal is to use it for feedback and to show it’s a tool to the students, because fortunately or unfortunately depending on your opinion, it’s here to stay in one form or another. I want to teach students to use it to help them set up for the final product, not be the final product,” Olin said.

After learning about Julius Cesar and Alexander the Great, Olin had his students generate images with AI and vote on which they liked the best. By letting them use it more and more throughout the year, Olin hopes to teach responsibility with the technology.

“The temptation has to be there for students. Let’s say you have to write a paper,

and you have to go through the whole process of planning it, creating an outline for

your paper, etc. As a student, you can writea prompt and it’s taken care of for you.”

A platform geared towards teachers, MagicSchool AI creates resources that can benefit a wide variety of students and provides helpful classroom materials. After asking teachers where and what they teach, they can simply put in the lesson and what kind of material they want: for example, a worksheet, presentation, student feedback or a quiz. Teachers can additionally add standards for the lesson to meet, specific inclusions such as group work or upload a file to better inform the lesson’s outcome.

“I use AI as a tool so it never creates an entire thing. I sometimes have it help me with giving feedback on writing. For DBQs (document-based questions), I’m using it to partially help me give feedback on specific things using the rubric I created. That helps me in coalescing my ideas about what students are writing and how they did. I’m not necessarily going to take the grade it gives them, but I’m going to use it as a backstop to help me,” Olin said.

AP Government and AP Macroeconomics teacher Tommy Houseman says the technology helps him cut down on his time spent lesson planning, leaving him with more time to grade papers or review work.

“It is especially helpful in terms of reducing my overall workload and allowing me to focus on other things. With the help or aid from ChatGPT, what would take me a planning period takes me five seconds to type it in and 20 seconds for it to create,” Houseman said.

ChatGPT helps Houseman make quizzes for his AP Macroeconomic classes, and then he checks them for accuracy after the fact. He predicts there will be some kind of adjustments schools make to integrate the technology into classrooms while teaching students to use it responsibly and keep teachers relevant.

“I think with this technology, there’s no putting the cat back in the bag or the genie back in the bottle, so I think, like every other technology, it’s how we are going to incorporate it,” Houseman said.

Despite the fact that AI has been helpful for teachers, difficulties arise when it comes to students. Houseman has started to use more traditional paperwork in contrast to work online, and many teachers use AI checkers, most popular being GPTZero, to ensure their students’ work is their own.

Along with GPTZero, other teachers check document revision histories and the Draftback Chrome extension in work documents such as Google Docs or Google Slides. Draftback allows one to play back the edits that took place on the document and view the time spent writing on the document. Google’s own revision history option is similar, showing what was written on the document by who at various times.

“The reality is all of us have essentially the answers to most of the questions about any academic subject at our fingertips with AI technology. My concern is it’s going to impact what is already difficult, like getting kids to focus, to take the classes and learn the information. AI will make our job as teachers even more difficult,” Houseman said.

Both Olin and Houseman agree that although AI is a helpful productivity tool, it is not a foolproof technology and still makes mistakes.

“We have to be particularly careful. My fear as an educator is you get folks who are just ‘okay, let me write this prompt’ and it spits it out, and then not reviewing it and not checking it. We have to be aware of the fact that even if we’re utilizing this tool, it’s still incumbent upon us to go back and review this information to make sure that our students are getting what’s correct,” Houseman said.

Jacob Lonsford, a major in social studies education at the University of Georgia, feels that AI doesn’t benefit those using it to help them learn because it does all of the work for them.

“I believe that for the purpose of doing school work and the point of going to school or earning a degree is that you’re learning as you go. You’re working your mind, and we think of the brain as a muscle. To grow it, you have to use it and actually work with it. If you are just using AI for your assignment, you’re not actually using your brain. You’re not working that muscle,” Lonsford said.

Cedar Shoals senior Emma Van Cantfort is strongly opposed to AI use. While she understands that those with learning disabilities or verbal/vision impairments can benefit from AI, she feels that the average student should stay away from using it. Van Cantfort stresses that when feeling stuck, going to the teachers will be the best option, for example with an idea for a project in class.

YOU MAY LIKE:

Striving for simplicity: AI and the destruction of what makes us “human”

By Aislynn Chau

“Half the time, teachers have a million ideas for you. If you ask them, ‘hey, what would a good project look like to you?’ or ‘what is something that you have never seen?’ I guarantee you every single time I’ve asked that, a teacher has been like, ‘oh, the kids have read this. Oh, I’d love to see that.’ The teachers want you to want to learn,” Van Cantfort said.

When the topic is brought up in class, Van Cantfort feels as though many students are tentative to admit to using AI tech. She points out that if one uses something regularly enough, they should be able to back it up and be confident.

“When you say that you don’t use AI, you can literally see people’s entire body shift and feel like they need to defend their use of it, especially like ChatGPT and stuff. They’re like, ‘oh, I don’t actually use it to cheat, I use it to take notes better or to figure out formulas.’ And I can understand some of that, but if you feel like you have to defend it and your entire body language shifts when it’s brought up, you might need to do a deeper internal look,” Van Cantfort said.

The most common student uses for AI that do not involve directly cheating are summarizing text, making notes or studying. Although she recognizes that it may help save time, especially in higher education, literature teacher Brittany Blumenstock emphasizes that the information or quotes AI gives you might not be correct, like textual evidence that is made up or false links for sources.

“I don’t think I would be upset if they used it to give me bullet points, digested that information and then, in turn, wrote their own paragraph. But what do you do if the AI is not correct, and you had nothing to double check if you hadn’t read over it yourself? I would think a great use would be to read it yourself and then to ask it for a summary, and then you can compare notes,” Blumenstock said.

Both Houseman and Blumenstock recognize that AI is a new technology in classrooms that will eventually have to integrate into them over time. Blumenstock has made the comparison of AI to calculators, and how something that was once seen as a shortcut has become a regularly used technology.

“A lot of math teachers and people in education were up in arms against the use of calculators in the classroom because they said it would take the thinking away from learning. Kids wouldn’t be able to do math anymore because a calculator would be doing all the math for them. But today, they’re so common in a math classroom, it’s only on certain assignments that you have no calculator, but it’s interwoven into math. So what’s ELA going to look like in 50 years? Is AI going to be interwoven into it? Is it going to end up with us needing to be doing different assignments entirely?” Blumenstock said.

Joshua Dumont, math department, opposes the use of AI. He claims that although some students use it to help them when they get stuck on work, unless they go through the process and do other practice themselves, they aren’t actually learning anything. Rather than just asking for the answer, Dumont encourages them to do the practice themselves, even if it’s hard because it’s part of the learning process.

“Your mental muscles become weak and then you can’t use them. You think you have a skill, and then let’s say you get a job that relies on that, and you don’t have it. You can’t actually do this job that you just got,” Dumont said. “You think that you’ve learned the thing because you’ve looked at AI answers to some questions while you were studying. It’s time for the test, and ‘I don’t have my AI on the test! I actually didn’t learn how to do this, so I failed!’ It’s thinking that you know something that you don’t, because you didn’t actually learn anything while using it.”