Learning Loss: CCSD shows signs of a national problem

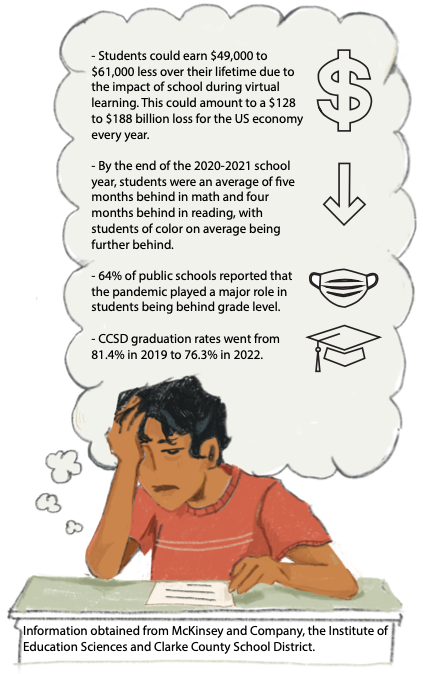

On Sept. 1, The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) released the 2022 scores for their long-term trend assessment test, which is administered biannually to 9-year-olds across the country. It found the greatest drop in average reading scores since 1990 and the first drop in average math scores since the testing began in the 1970s.

The damage caused by virtual learning between March 2020 and April 2021 can also be seen at the county level. Clarke County’s College and Career Ready Performance Index (CCRPI) scores from 2022 show decreases in their content mastery from 2019. Elementary schools decreased by 6.1 points, middle schools by 6.6 points and high schools by 1.8 points.

“It’s very difficult to learn in a virtual environment, (it’s) such a vacuum. Once everybody became a black box and no expression was being shown, life was difficult,” Cynthia Hoover, a Cedar math teacher of six years, said.

Emerging Math Deficits

The amount of Georgia third through eighth graders characterized as beginning learners by math Milestones testing increased from 33% in 2019 to 41.7% in 2022.

During virtual learning Hoover says the math department strategically altered their curriculum and communicated with each other about what their students would be missing in the future.

“If anything was cut, it was decided because they’re going to turn around and reteach it next year. We felt that you could go a little lighter on those things,” Hoover said. “It was far less than I would have liked to have been able to get to, but I did feel at the end that we covered everything that was absolutely necessary to say you learned geometry this year.”

Jennifer Schmidt, math department teacher of 14 years at Cedar, estimates she covered about 85% of her Algebra l material. These condensed curriculums and the challenges of learning virtually have resulted in gaps in students’ math skills. But, as the math Milestones data suggests, Hoover and Schmidt are noticing these gaps less this year compared to last. Milestones scores show the amount of students considered proficient or distinguished learners increased from 16.4% in 2021 to 26.8% in 2022. That said, their students are still missing more knowledge than usual.

“Some of the content that we show them (students) in ninth grade, we just assume they learned in middle school,” Schmidt said. “We realized that they don’t know this material because normally it’s covered in a grade they were home for.”

Sophomore Maria Payne learned virtually in eight grade and says she feels an expectation to know math concepts she missed.

“One of my teachers always expects us to know things from the eighth grade. I was like, ‘I didn’t learn anything in eighth grade,’” Payne said.

A RAND Education and Labor study found that only 19% of teachers in a hybrid learning setting during the 2020-21 school year said they were able to cover all or nearly all of their curriculum.

Elementary school students may have missed more curriculum than older students due to the amount of guidance they need. Amanda Carrithers, a 5th grade teacher at Gaines Elementary School, thinks she covered about half of her math units because of lack of engagement and the confusing transitions between learning models.

“I honestly just thought that all but maybe two of my students should have moved on from fifth grade that year,” Carrithers said. “It was an overall knowledge gap in their curriculum, they just didn’t get it.”

Tracy Vandiver, a collaborative special education teacher who taught kindergarten at Barnett Shoals Elementary School during virtual learning, believes she and her co-teacher covered about 30% of what they typically would. Allison Still, who has been teaching kindergarten for 15 years at Whit Davis Elementary school, estimates a more a more generous 70%. Content missed from these curriculums could result in gaps in lower level math skills, which Hoover says could create difficulty later on.

“We move out of concrete mathematics, which is all of elementary and middle school, and we start moving into abstract thoughts and processes. But then you have to apply that (basic skills). If you’re missing some of these basic skills, it’s going to make life a little difficult,” Hoover said.

Reading Difficulties

CCRPI data showed decreases in the literacy rate of CCSD students across age groups. Middle and elementary schools decreased by about 7 points and high schools by around 10 points from 2019 to 2022.

Still guesses the kindergarteners she taught virtually are now struggling with reading. Vandiver notices this struggle, particularly when it comes to the basic skills of current fifth graders.

“Our biggest obstacle this year is comprehension — how to read something and then derive facts from it and how to speak and communicate clearly,” Vandiver said.

Bryan Moore, English department chair at Cedar, says his students are regaining the reading and writing stamina he thinks suffered during virtual learning.

“It’s always a struggle to keep some kids’ attention in class, but as we get further away from virtual instruction, kids get more used to being in class and responsibilities,” Moore said. “What is kind of the muscle memory of being in the classroom is taking a bit of time but I can see it coming back.”

Moore questions the level of damage virtual learning caused in high schoolers, but he emphasized the danger of reading learning loss in elementary school students and referenced studies on the matter. A 2012 study by the Annie E. Casey Foundation concluded that children not proficient in reading by third grade were four times less likely to graduate on time.

“I think there’s a group of kids we have to keep an eye on that didn’t have that direct reading instruction at a time when it’s most critical,” Moore said. “I think that their gap may endure without some real enforcement in that area.”

Though the NAEP data found decreases in test scores, Georgia’s average 2022 math and reading scores did not significantly differ from their 2019 scores by NAEP criteria. Like this evaluation suggests, Vandiver doesn’t think learning loss will be necessarily detrimental for students, even young ones. Drawing from her own experience of missing fourth grade because of medical issues, she thinks the effects of learning loss will depend on a student’s situation.

“I don’t think it ruined my life. I went to college and got four degrees. But I was also very driven as a learner. Just because I didn’t go to fourth grade didn’t mean I wasn’t still learning and reading. The kids who are having problems are the ones that don’t have access to learning and don’t have people to push them forward,” Vandiver said.

Increasing gaps

According to the NAEP data, historically disadvantaged students are most negatively affected by virtual learning. Gaps between higher and lower income students have widened as well as racial disparities. One explanation for this development is that Black and Hispanic students spent more time on average learning virtually than white students according to research from 2020 by McKinsey and Company. Increased time spent virtually was linked to lower test scores in 2022 by data from Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research.

Another explanation is that economically disadvantaged students and students of color already fared worse on standardized testing, so virtual learning only deepened an already existing problem. Hoover describes the pandemic as a catalyst revealing these preexisting gaps.

“Any student who comes into something like the pandemic with a lack of skills to begin with is going to struggle even more,” Hoover said. “Then you come back and everybody’s charging at a regular pace. And these kids are like, ‘Wait, I really don’t even know.’ Now you’ve got a bigger gap because they’re really challenged to keep up with the original pace of the curriculum.”

Though some students were less affected by learning virtually, NAEP data shows decreases in all performance percentiles. Carrithers has noticed this in her own classroom, attributing decreases to developmental issues.

“They lost a lot of social-emotional stuff in that time. I have some really bright students that will walk out of the classroom when things get hard because they could turn off their computer when things got hard,” Carrithers said.

Social-emotional effects

A 2022 survey by the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) found that over 80% of public schools agreed that the behavioral and socioemotional development of their students was negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though Vandiver’s own class has minimal behavioral issues, she has noticed an increase in disruptive and emotionally stunted behavior among younger students.

“We see our little kids not able to play together nicely, not able to listen and talking back to teachers. I’m not saying this is everybody, but they’re having a really difficult time,” Vandiver said.

Vandiver thinks there should have been greater emphasis placed on helping students recover socially and emotionally when they returned to in-person school.

“We just jumped right back into the thick of things without really addressing the social emotional aspect,” Vandiver said. “Focusing on that and giving them a little bit more time to ease back in instead of just jumping into the academics would’ve helped with the meltdowns.”

Due to their age, Carrithers believes her students’ social-emotional skills were more damaged by virtual learning than their academic abilities.

“Coping skills are very difficult for kids. Stamina is very difficult for kids. They came into fifth grade but in many ways they are still third graders. Their development emotionally has been staggered and it is very noticeable,” Carrithers said.

Moore saw similar behavioral struggles in high schoolers, but he says there have been significant improvements this year compared to last. He attributes this progress to the maturity and past experience of high schoolers.

“Last year was a crap show in a lot of ways, but that was the transitory year,” Moore said. “I’ve seen a lot of difference this year as far as student adjustment to being back in school.”

Another effect of virtual learning has been an increased dependency on technology. Vandiver notices students have lower handwriting ability and fine motor skills. The IES survey found that 42% of public schools reported that prohibited electronic use had increased because of virtual learning’s influence.

“We’ve had a phone issue for years but not to the extent it is now,” Schmidt said. “I can’t speak for other subjects but Algebra I is very difficult to do when you’re sitting on your phone.”

Recovering from learning loss

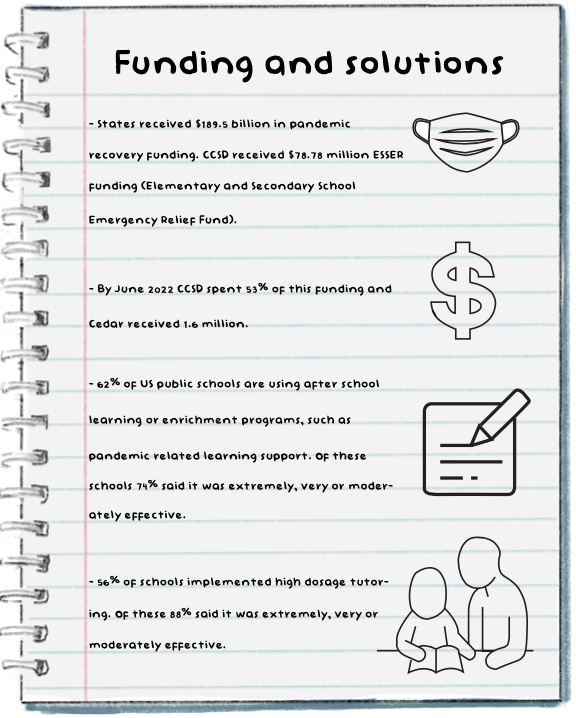

With the federal government making the largest single investment in schools ever, $190 billion for student recovery, solutions to learning loss are a focus. CCSD received $78.78 million, with $1.6 million going to Cedar.

Madison Steen, English department, thinks closing learning gaps should start with intentional, well planned lessons followed up with programs like the Pathways to Success Program (PSP). At Cedar, PSP enables students to stay after school three days a week for tutoring in two hour periods. Saturday school is also offered. These sessions involve mini-lessons that reinforce important concepts, individualized reteaching and focused time for completing assignments. Steen thinks the program is helpful in addressing learning gaps.

“I think it’s giving students an ability to believe in themselves that they can actually pass when you sit down one on one and help them,” Steen said.

In elementary schools, the Early Intervention Program (EIP) takes students out of their classes to work in smaller groups. Students in need of additional help are chosen based on test scores, completing the same activities as their peers but with more depth and personalization.

Vandiver thinks the program is beneficial but dislikes separating students.

“I think they (students) would rather stay in our class. They miss out on a lot of fun activities at times and they think it is unfair. I wish that our kids could all be together because it makes community, but I do think it’s helping them,” Vandiver said.

Virtual learning has resulted in a student body with more varied skill sets than usual. As a result, Andrea Kahl, a teacher of seven years working at Hilsman Middle school, thinks breaking up students into small groups is an important solution to learning loss.

“Right now it’s really put on the teacher. You identify the kids in your class, you pull a small group, but you still need to manage everybody else. I think a more effective way would be to actually remove them into a smaller setting,” Kahl said.

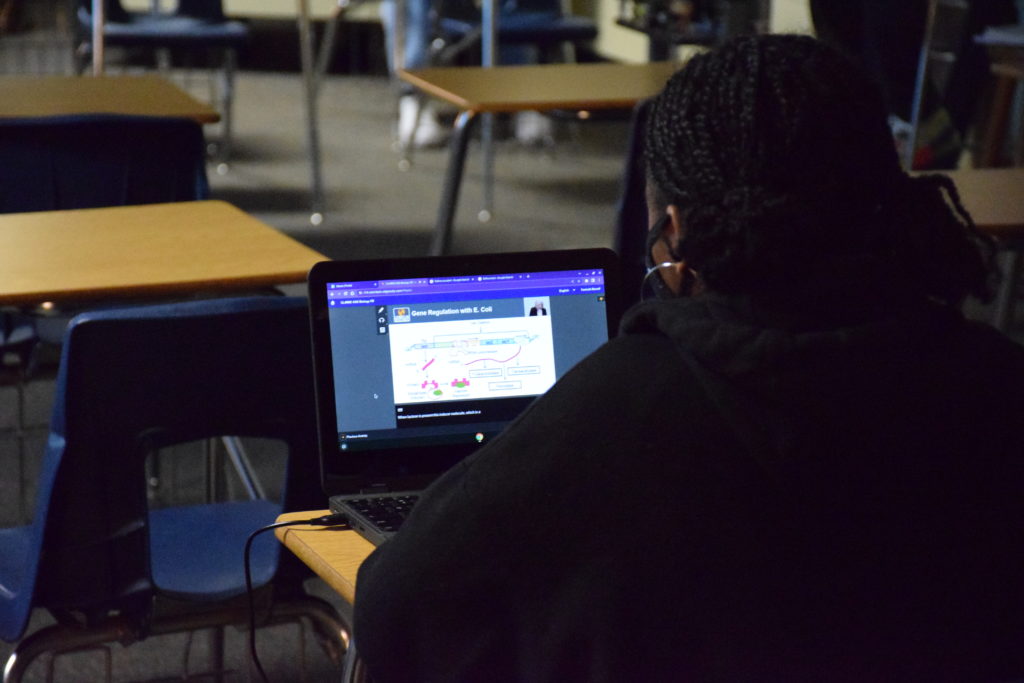

Along with struggling with missed learning, some high school students, like juniors Jameria Wise and Layrn Cross, have failed classes from virtual learning on their transcripts. These classes lowered their GPA’s, limiting their future opportunities.

“That was probably the first time I failed a couple of classes. It was really hard and it messed up my GPA. So when we came back to in-person I was stuck trying to fix stuff,” Cross said. “But I feel like if none of that happened, I would have done all of my classes on time, even taken extra classes.”

To fix these grades Cross and Wise took advantage of credit recovery through Edgenuity. Though both benefited from the experience, Wise thinks more could be done to help students avoid the same traps from virtual learning.

“I finished before my classmates. It’s basically your pace, which isn’t good because there are still kids stuck in that class. I just think they should enforce things a little bit,” Wise said.

Carrithers expressed frustration over feeling that not enough was done to address the immediate and continued effects of virtual learning on children. She wishes holding more students back would’ve been explored more as a plausible option.

“I think everybody should have admitted we failed our kids that year and it wasn’t their fault. We just need to back it up now and do what we can so that they’re ready for their next step because they were not ready coming into this year,” Carrither said.

Vandiver feels there was a push to help students recover in the immediate aftermath of virtual learning, but that it sometimes involved the district buying new programs that put pressure on teachers to go to trainings without the district considering their feedback. CCSD Superintendent Robbie Hooker agrees that this isn’t the best approach.

“I think if you’re going to buy programs, you better monitor to see the effectiveness of it. Is it right for our kids? And if not stop using it,” Hooker said in a press conference with BluePrints. “Some school systems brought various programs thinking that it’s going to help. But I don’t think programs help, I think good old fashioned teaching helps.”

Also acknowledging the shortcomings of relying on new programs, Carrithers thinks students ultimately just need room and support to recover.

“If we really want to help our children, we need to take some lessons instead of trying to pretend that we can just plow forward and buy programs. Just let teachers teach and really get enough teachers and support staff in the building,” Carrithers said. “Help kids develop the way they need to, instead of just pushing and pushing them through.”