Standardized testing: an inequitable system faces a crossroads

All American students have experienced the symptoms: sweaty palms, sudden amnesia, general angst. A pillar of education, standardized tests have evaluated student performance for decades. However, questions of testing inequity have been growing since its advent, and thanks to COVID-19, the system is one of many forced to alter in the last two years.

State-sanctioned performance exams

Testing is ingrained into American achievement evaluation. The average U.S. student takes 112 standardized tests throughout their educational career from pre-K to 12th grade, whereas students in other countries whose students outperform U.S. students on global exams are tested an average of three times.

As required by the United States Department of Education, Georgia administers a set of standardized tests unique to the state every year: the Milestones. Grades three through eight take the end of grade (EOG) exams; and grades nine through 12 take the end of course (EOC) tests, but only in some classes, like biology and economics. The tests measure students’ mastery of Georgia standards, and EOCs serve as final exams that determine 20% of final grades. An additional interim exam is given during the semester to measure progress towards preparedness for the EOC.

A data analysis follows each interim administration. Bryan Moore, English department chair, has participated in the process throughout his 26 years at Cedar Shoals. Every time interim results are released, he says he and his colleagues sit down with a coach to evaluate how their students scored on curriculum standards, though he doesn’t always put much value into results they examine.

“I trust more what I see of their performance in my class. Some kids aren’t good test takers, some find it hard to motivate themselves for that. If every kid took the test as seriously as possible every time that might be some valid data, but there’s too many factors that go into it that I can’t draw too many conclusions. Especially in English, because we don’t think in a multiple choice kind of way,” Moore said. “You’re basically saying a two hour test given one time is supposed to be valid data instead of the performance of a kid over 18 weeks.”

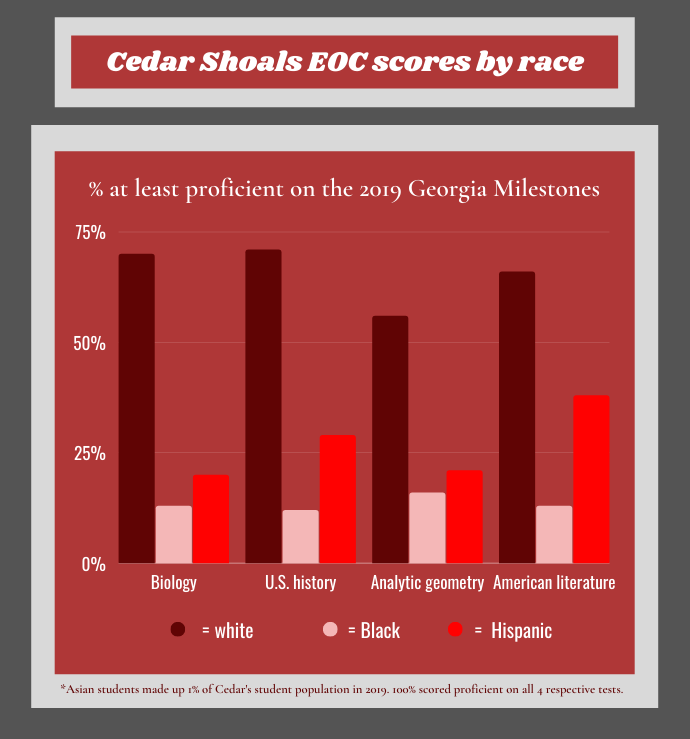

The socioeconomic and racial inequalities of testing are manifested in Clarke County School District, where Black students are an average of 3.4 grade levels below white students, and racial achievement gaps are double that of the state. In a school district with 79% students of color and nearly 50% of Black families and 45% of Hispanic families living in poverty, just one third of students were proficient on the Milestones in 2019. The only test in which CCSD matched the state average was the Coordinate Algebra EOC, taken by 8th graders in the accelerated program.

CCSD Director of Assessment Dr. Robert Ezekiel says inequity in testing is being addressed at the district and school levels.

“Schools are focusing on equity. They are also focused on teaching the standard. Looking at achievement data, we’re looking at it by race, by gender, different demographics to determine who is performing and how they perform,” Ezekiel said. “Teachers are working collaboratively to design lessons to address any achievement gaps that are going on across the whole district.”

Teachers receive curriculum standards from the state department of education that determines the topics they should cover in class. From there they work together to create lessons, materials and their own classroom assessments to teach the standards. The EOC assesses these standards, but teachers play no role in designing the questions. Dr. Margaret Morgan, math department, would prefer the exam be produced by her and her colleagues.

“I don’t really understand how it’s written. I don’t understand what the purpose of the questions are,” Morgan said. “A departmental final where all the teachers decide on the questions or even a district-wide final where all the teachers get together and decide what’s going to be on it, I think that would have the same level of accountability with more transparency for teachers.”

College readiness exams

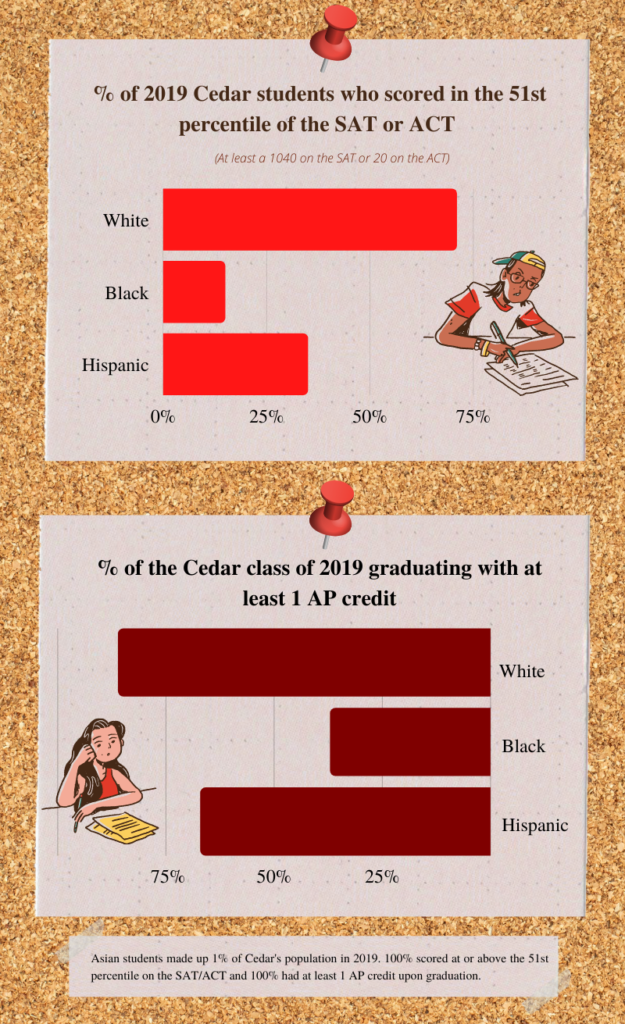

All Georgia students take the EOCs and interims. Additionally, in Georgia and nationwide, Advanced Placement students take the AP exam to determine if they will receive college credit, and college-bound students take the SAT or ACT to measure readiness for higher education.

Writings by Carl Brigham, inventor of the SAT and AP tests, indicate a eugenicist agenda. In his book “A Study of American Intelligence,” Brigham wrote that the SAT would avert “the continued propagation of defective strains in the present population,” including the “infiltration of white blood into the Negro.” He rationalized that “the Nordic race group” would outperform students of color, giving reason to deny them admission to prestigious colleges and prevent “promiscuous intermingling” between races.

A University of California Berkeley study found that today, more than one third of variance in a student’s SAT score can be credited to their family’s income, parental education and race or ethnicity. Brigham himself eventually wrote in an unpublished manuscript that test scores have less to do with intelligence and more measure “a composite including schooling, family background, familiarity with English and everything else, relevant and irrelevant.”

Morgan has witnessed the socioeconomic bias of the SAT as a parent and Cedar educator.

“I know my son didn’t learn all the math he needed to last year. He doesn’t want to sit down with me and have me teach it to him, so I signed him up for a $1,000 SAT class,” Morgan said. “Most parents couldn’t afford to pay for that class. That’s a problem.”

She recalls a standardized test preparation course she hosted with the College Factory.

“It was Saturday mornings and cost $25, and still the people who signed up for it were much more middle, upper middle class and white. Definitely our lower socioeconomic students are at a disadvantage when it comes to standardized testing,” Morgan said.

Senior Max Whitford says he didn’t realize the disparities in CCSD until meeting students from outside the district. A conversation over the summer with a friend from Gwinnett County sticks out to him.

“He was like, ‘Oh, I only took the SAT once I got like a 1560.’ I was like, ‘You got a what?’ It’s so crazy to me, the difference in grades based on economic ability,” Whitford said. “If you take a kid with good internet and a stable family in a nice house, and then you take a kid who has to go to the public library for internet and is using a school Chromebook, and they both take the SAT, who are you going to expect to do better?”

The SAT and ACT are created, administered and measured by the standards by the College Board and ACT, Inc., which are private companies. Though unable to change the content, Cedar is addressing the achievement gap by increasing the number of times students interact with the tests. Students can take the PSAT in the fall and the ACT in the spring at Cedar, in an environment they’re familiar with. CCSD students also receive fee waivers for the $55 SAT, $60 ACT and $96 AP test, and a college counselor is available at both high schools to assist.

To prepare his students for the AP test, Moore incorporates multiple choice questions into his lessons, though he is generally adverse to using them to assess comprehension. Half of the AP Literature exam is multiple choice.

“On the AP test, the multiple choice questions can be really picky and unfair sometimes. That’s not a good way to assess how you understand literature. I just feel like they (College Board) don’t look holistically at a piece, they judge things through those multiple choice questions that kind of miss the plot, and they’re really, really hard,” Moore said. “When I do the AP test run through with the kids, I take the same test and I struggle with some of those, then I’ll look at their explanations and I get angry and indignant.”

The AP test is significant — it determines if hard work will be rewarded with a college credit. Moore’s more meaningful mission of embarking into literary scholarship is a challenge to balance with the burden of standardized test preparation.

“I tell the kids this class has two different goals. There is the goal of that AP test, but I don’t want to make the entire class about that. I still value literature and what we can explore and gain through that study,” Moore said. “It’s always a balance of preparing the kids for the test, but also finding some kind of peace with what you’re doing and not making the whole class test prep.”

COVID-19’s impact

In response to COVID-19’s unpredictability, many colleges have waived standardized testing for the 2021-22 admissions season, some permanently. Notable outliers the University of Georgia and the Georgia Institute of Technology will require SAT or ACT scores. Because of her work outside of Cedar Shoals with ULead, an organization that assists undocumented Latinx students with applying for college and scholarships, Associate Principal of Instruction Dr. Melissa Pérez says this is a positive change.

“A lot of our Latinx students that are English learners and students from lower socioeconomic status don’t have access to SAT/ACT tutoring or the resources to take private classes,” Pérez said. “I’ve definitely seen a discrepancy between a student’s GPA, what I think their ability is and what’s reflected on their SAT and ACT score. Those students usually either try to apply to score-optional schools or schools that offer scholarships that are not based on the test score that recognize that there is a bias in those tests.”

ULead provides tutoring and support, but Pérez has found her students are hindered by the arbitrary time and financial commitments required of high SAT or ACT scores.

“As hard as we try to provide the prep books and the free tutoring to help prepare students, sometimes it’s just a matter of ‘Well, my family needs me to work, I don’t have the time available.’ It’s not a matter of ‘I don’t find the test important or my family doesn’t.’ It’s a matter of need,” Pérez said.

Boston College’s National Board on Educational Testing and Public Policy has placed the value of the standardized testing market between $400 and $700 million. Parents spent $13.1 billion on test preparation in 2015, and the College Board, which creates and administers the SAT and AP exams, boasted a revenue of $1.2 billion in 2020.

“The purpose of standardized tests is to make money, so I don’t know that that whole system can shift that much. When wealthier white kids do better on these tests, that’s good for them because those are the people that are going to pay for the test, those are the parents who are going to spend the money on a TI-84 (calculator). There’s no point in owning a TI-84 anymore except for taking the AP exam and other standardized tests, because Desmos is a much better graphing calculator than the TI-84,” Morgan said.

COVID-19 didn’t just uproot the college prep exams. Spring 2020 Milestones were cancelled. After being twice denied of waiving the Spring 2021 exams, State Superintendent Richard Woods designated the Milestones as optional, and EOCs weighed just .01% of final grades. Communication thus far indicates that Georgia students will revert back to the traditional Milestones this Spring. Pérez worries this decision might overlook lingering effects of virtual learning.

“At the beginning of the school year we were operating under the assumption that everything was back to normal. We had to adjust and realize that COVID is very much still with us,” Pérez said. “I think going back to the 20% on the state’s end is in some ways a failure to recognize that we’re still in a pandemic, and that we’re still dealing with the learning losses. It isn’t considerate or sensitive to that reality.”

Junior Destiny Strickland has suffered from test anxiety throughout her educational career. Though she appreciates testing for its feedback, reduced weight for the EOC would account for students like her.

“Testing has definitely made me realize the things I should spend more time on, but it has also affected my esteem and grades. If I fail a test it makes me overthink,” Strickland said. “Last year was hard for me being online, so the fact that it didn’t count as much gave me some relief. This year may be stressful considering it weighs more and will affect your grade for better or for worse.”

Meghan Frick, Director of Communications for the Georgia Department of Education (GADOE), says while the state would be willing to request to waive federal testing requirements, “it is unlikely the same administration that declined last year’s waiver request would approve one this year — so we have to be prepared to administer the test.”

The portion of CCSD students who opted to take the Spring 2021 EOCs ranged from 2% of U.S. history students to 49% of students taking physical science, the majority of which were advanced 8th graders who had been in-person more consistently than high schoolers. Students across Georgia showed a decrease in scores in most subjects. While this decline could be attributed to learning disruptions due to the pandemic, GADOE urges interpreters to use a grain of salt when analyzing scores.

GADOE is working to address learning gaps from last year, according to Frick. The content will not be different, but districts have been provided with tools to help students catch up, including formative assessments to predict Milestones scores, new Academic Recovery Specialists to assist school leaders, more summer and afterschool programs and federal relief funds specifically for remediating learning loss.

Students of color were most impaired by COVID-19. In Fall 2020, after less than a year of virtual learning, students in school districts that predominantly serve students of color scored just 59% of the historical average in math and 77% of the historical average in reading on the iReady diagnostic examinations. McKinsey & Company estimates that students of color lost 12 to 16 months of mathematics learning from March 2020 to June 2021, whereas white students lost five to nine. Now, with Milestones returning to their full gravity, a concern arises: how CCSD students — already disadvantaged and likely to have learning gaps — will test this year and in those to come.

“It’s just going to get worse. These effects are only going to become more and more prevalent as the people who were elementary online eventually get to high school and start taking standardized tests,” Whitford said. “The tests are just going to display learning gaps that we have as a school, as a county, as a nation.”